In this article I explore a question that has intrigued me for years: Why does Kurma avatar—the tortoise incarnation of Sri Maha Vishnu—remain oddly invisible in the lived religious landscape, appearing mainly as a brief scene in Dashavatara panels and temple carvings, yet lacking large independent temples, widespread popular worship, or a strong presence in contemporary culture? This piece is based on my long study and visits to places like Srikurmam and on centuries-old sources such as the Kurma Purana. I wrote and narrated a video on the subject for Project Shivoham, and here I have expanded that conversation into a full-length article to share the deeper layers: history, archaeology, symbolism, surviving shrines, rare iconographies, and the philosophical heart hidden behind the humble tortoise.

Table of Contents

- Outline: What this article will cover

- Introduction: The familiar story and the larger mystery

- Srikurmam: The only major temple where Vishnu is Kurma

- Shweta Kundam: A unique afterlife ritual site beside a Vishnu temple

- Rare iconographies: Vaikuntha Kamalaja and Vishnu Durga

- How the temple was saved: burial, sand, limestone and village devotion

- Childhood memories, living tortoises, and a temple that breathes

- The Kurma Purana: an underrated compendium

- Language and choice of words: Janardhana becomes Kurma

- Kurma, time, and the philosophical center

- Cross-cultural resonances: Srid Paho and the Sri Chakra on the back of the tortoise

- Why are there so few temples dedicated to Kurma?

- What Srikurmam teaches us about tradition and survival

- Ritual life at Srikurmam: what to expect

- Conserving the intangible: oral tradition, sthalapuranam, and living memory

- Reflections on symbolism: foundations, humility, and public memory

- Conclusion: Reclaiming Kurma’s place in our religious imagination

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

- Final thought

Outline: What this article will cover

- Introduction to Kurma avatar and its familiar role in Samudra Manthan

- Why Kurma seems absent from popular temple worship

- Srikurmam: the unique living temple of Kurma in Andhra Pradesh

- Shweta Kundam — the sacred lake and afterlife rites beside a Vishnu shrine

- Rare iconographies preserved at Srikurmam: Vaikuntha Kamalaja and Vishnu Durga

- How local devotion saved the shrine: the story of burial and resilience

- Kurma Purana: what it contains and why it matters

- Cross-cultural resonances: the tortoise in Buddhism and Shri Vidya

- Why there are few temples devoted solely to Kurma: symbolic and sociocultural reasons

- Rituals, ecology and living tradition: tortoises at the temple

- Conclusion and reflections

- FAQ

Introduction: The familiar story and the larger mystery

When most of us think of Kurma avatar, the image that comes to mind is the great cosmic churning—Samudra Manthan—where devas and asuras use Mount Mandara as the churning rod and Vasuki as the rope, yielding divine treasures: Lakshmi, Dhanvantari, Amrita, and even the origin of Rahu and Ketu. In temple panels, in miniature paintings of the Dashavatara, Kurma is always the second avatar; usually a tiny figure at the base of the scene, unnoticed, almost incidental.

But this is only half the story. The Kurma episode is not a minor subplot. It stands at the root of multiple narratives and festivals, at the origin of key gods and sacred objects, and even underpins the story-logic of Diwali as we celebrate it. Yet despite this foundational role, Kurma has no great modern public profile. No blockbuster films, no popular mythic cult movement, few devotional texts in circulation that center the form as an independent focus of worship. Why has an avatar that bears the weight of Mount Mandara and supports the very churning that births the gods been reduced to a decorative motif?

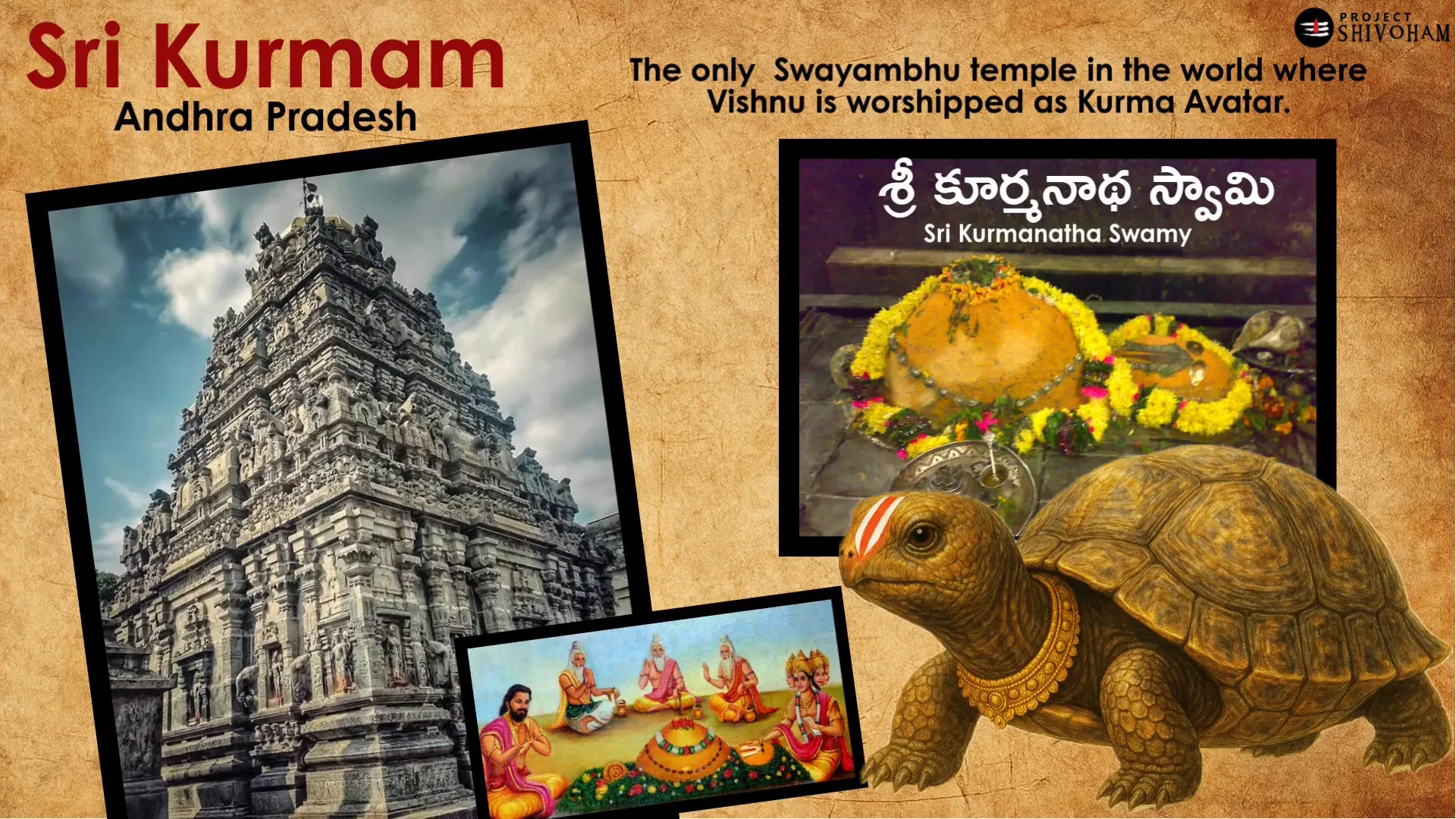

Srikurmam: The only major temple where Vishnu is Kurma

To answer that question, we must leave the stereotyped images and go to places that still conserve living memory. In the quiet coastal belt of Andhra Pradesh sits a remote village called Srikurmam. Here stands the only major temple in the world where Sri Maha Vishnu is worshipped in his Kurma form as Kurmanatha Swami.

What makes Srikurmam extraordinary is not only the deity but the form of the shrine: it is a swayambhu (self-manifested) sanctum whose sthalapuranam claims manifestation in the Krutha yuga. The Padma Purana has a prominent account about this site, tying the spot to antiquity and linking landscape features to mythic kings and deeds. When you visit Srikurmam—if you can—you feel a continuity that is rare: layered stones, quiet rituals, local memory, and, most tangibly, a temple composition that speaks of uninterrupted devotion across the centuries.

At Srikurmam, Vishnu is called Kurmana Dhaswami, the tortoise that bore Mount Mandara and became the bedrock for Samudra Manthan. The sanctity here is not derived from later literary embellishment alone; it is rooted in the place itself, in the lake beside it, in the very flora and fauna of the site—a living landscape that preserves an avatar in a way few other places do.

What does “swayambhu” mean in practice?

When a murtI (image) is called swayambhu, it implies self-manifestation—not carved by human hands but discovered, emerging from the earth. Such sanctums often carry the weight of older ritual traditions and are less dependent on royal patronage. Srikurmam’s claim to swayambhu status situates it as a locale where local devotion, not imperial temple-founding, is primary. That local rootedness accounts for some of the features we will examine: discreteness of the shrine, rituals tied to village lifeways, and the presence of unusual iconographies that survived because they were not on the state’s architectural maps to be destroyed or altered by large-scale political shifts.

Shweta Kundam: A unique afterlife ritual site beside a Vishnu temple

Beside the Srikurmam temple lies a small lake that Padma Purana explicitly ties to the site. The sthalapuranam says Sri Maha Vishnu created this lake with his Sudarshana chakra for the benefit of a king named Shweta Chakravarti in Krityudha. Today the pond still carries the name Shweta Kundam—an astonishing thread of living memory that anchors myth to geography.

What is striking—and indeed unique in Vaishnava contexts—is the practice that continues here: immersion of ashes and mortal remains. In most regions where Vishnu shrines are central, the cremation-and-immersion rituals revolve around Shiva-ksetras like Varanasi (Kashi) or other śakti kshetras. That Srikurmam hosts regular visarjan (immersion) rites at Shweta Kundam beside a Vishnu temple is exceptional. Locals even claim that bones thrown into the pond turn into stone—a mythic way to express what might be a real taphonomic process: long-term immersion can mineralize bones so they appear rock-like. Beyond the folkloric flourish, the sustained practice indicates a continuity of funerary ritual at this site that predates many modern settlement changes.

Such continuity is rare and significant. It suggests that Srikurmam, unlike many later royal-built Vishnu temples focused on the aesthetics of temple politics, preserved ritual lines that tie community life, death, and memory to the Kurma avatar in a way that millions of ritual participants have carried forward.

Rare iconographies: Vaikuntha Kamalaja and Vishnu Durga

Srikurmam is not only about a single, unusual deity. It preserves iconographic forms of Vishnu that are extremely rare or lost in mainstream practice.

One such form is Vaikuntha Kamalaja, a fused image of Vishnu and Mahalakshmi, a single murti where male and female principles are depicted together—an early form of Vaishnava devotion that articulates divine union. Vaikuntha Kamalaja statues and reliefs once existed across remote regions, including far northern pockets like Kashmir, but invasions and systematic temple-destruction erased many of those traditions. Much of what survives from such cults are fragmentary pieces in museums. To have a living tradition, or even relics, at Srikurmam is therefore a marker of exceptional continuity.

Equally intriguing is Vishnu Durga: an iconographic fusion where Durga is understood and worshipped as a manifestation of Vishnu. You encounter Vishnu Durga prominently in places like Vaishno Devi, and in small pockets across Tamil Nadu, but at Srikurmam the presence of a living Durga allied wholly with Vishnu—the Vishnu Durga—is rare. Here Ma Durga, revered as Sri Maha Vishnu in the form of Durga, stands alongside Kurmanaatha Swami. That fusion—Durga as Vishnu—reveals a theological elasticity and a syncretic devotion that survived at the margins when it was extinguished elsewhere.

These iconographies matter because they hint at how Vishnu was worshipped before the homogenizing forces of later medieval temple ritual, before specific sectarian identities hardened. They hint at a time when iconography and doctrine were fluid: gods fused, attributes traversed, and local forms persisted through familial and village worship rather than through monumental royal sponsorship. Srikurmam preserves that fluid, pre-modern world.

How the temple was saved: burial, sand, limestone and village devotion

When we talk about temple survival across the Indian subcontinent, the common narrative is that the south preserved tradition while the north bore the brunt of invasions. That binary is too simple. Temples in the south were also attacked, and many were destroyed. But when large gopurams or vast complexes attracted attention, smaller shrines were sometimes spared—by chance or strategy.

Srikurmam’s survival story deserves attention for its poignancy. The sanctum and its modest gopuram (about twenty to twenty five feet high) were intentionally buried under heaps of sand and limestone powder by the local population during the era of invasions. The purpose was simple and profound: conceal what mattered so the marauding armies would not find and desecrate it. Hundreds of villagers labored together in secrecy, covering the shrine and its deities with earth until the place was invisible to outsiders.

What remains visible in the carvings today—the powdery residues, the subtle stains along the stones—are fingerprints of that rescue. These are not merely stains; they are history. They testify to ordinary people placing their devotion above everything and coordinating an act of collective preservation that allowed later generations to rediscover and restore the temple.

This kind of resilience—preserving the sacred through hiding rather than through force—tells us something crucial: that not all survival was due to kings and armies. Sometimes it was the quiet, unpublicized devotion of villagers that preserved objects of worship and the habits that go with them. Srikurmam is living evidence that preservation is as often grassroots as it is royal.

Childhood memories, living tortoises, and a temple that breathes

I first visited Srikurmam when I was about twelve or thirteen. My earliest memories are vivid and unadorned: the temple courtyard alive with tortoises. Not one or two, but dozens scattered everywhere—from palm-sized youngsters that could fit in your pocket to older, larger shelled creatures moving deliberately across the stone floors and the tank banks.

Those tortoises were not kept as pets. They were wild. They made their homes in the pond and temple surroundings as if the deity himself had filled the precincts with his own symbol. For children, this made the visit to Srikurmam special; there was a tangible, living symbol of the Kurma avatar underfoot. We walked carefully, because any misstep could crush a living sign of the god’s presence. Those memories are not trivial: they show how myth, reuse of space, and ecological patterns intersect to create a living tradition.

Over decades, the village and the lake grew together. The tortoises remain a part of the sacred ecology of the place. They are not fenced off but live freely, respected as embodiments of the deity’s presence. The living tortoise population is itself a ritual resource: a continuous, natural reminder of the Kurmavatar that no temple panel could equal.

The Kurma Purana: an underrated compendium

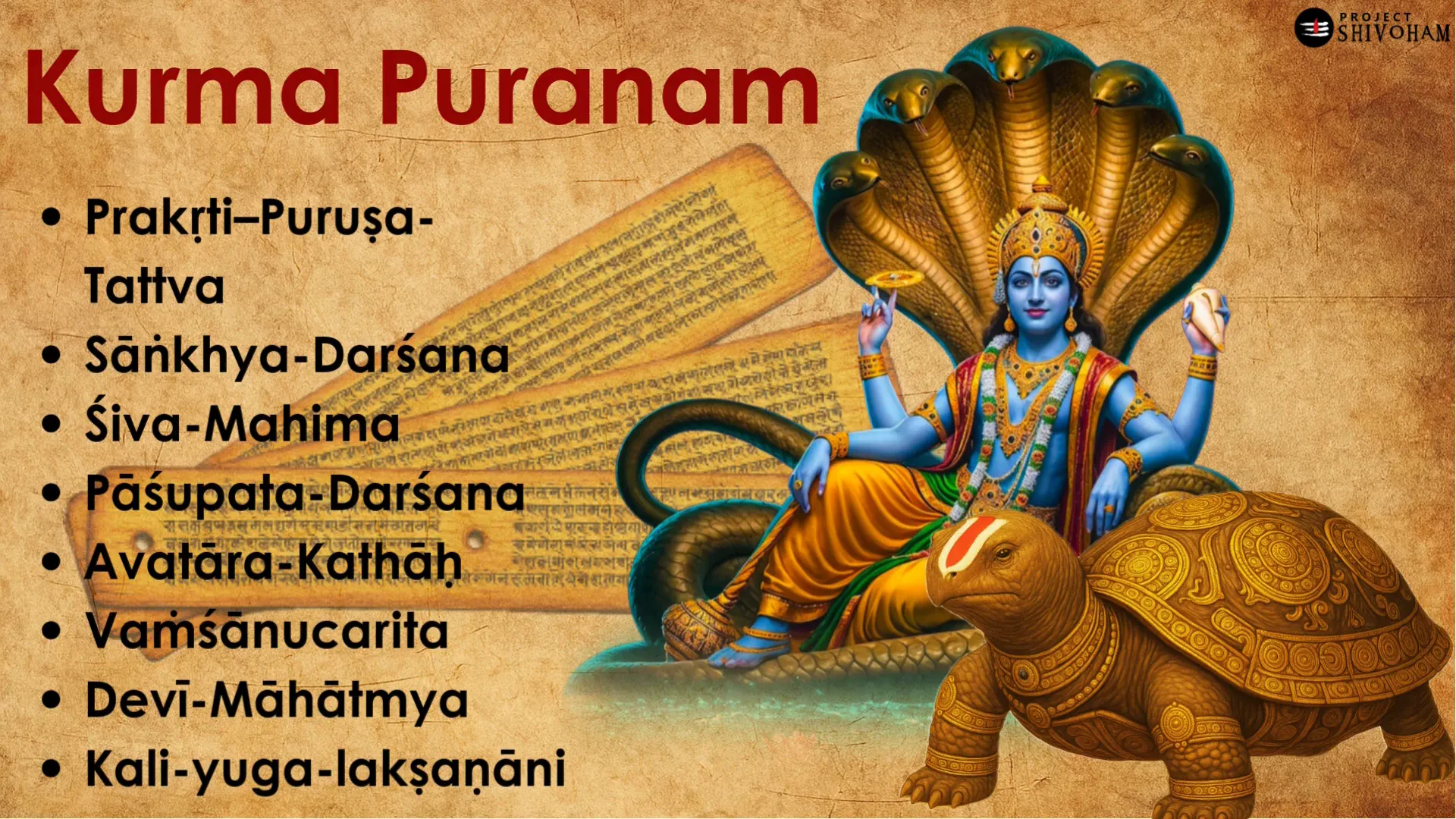

Among the eighteen Mahapuranas, the Kurma Purana is a text dedicated to the tortoise incarnation. For most lay readers, the big names like Vishnu Purana, Bhagavata Purana, Shiva Purana and Skanda Purana are familiar. The Kurma Purana, however, is less commonly cited in our contemporary religious discourse. Yet its horizons are vast and its content surprisingly plural.

The Kurma Purana contains the narrative of Samudra Manthan and the Kurma avatar, but it does not stop at mythic narration. It explores sarga-praty-sarga-pralaya—the cycles of creation, dissolution and re-creation—and narrates other avatar stories, including the Varaha avatar where Vishnu rescues the earth. It contains the Daksha Yagna episode (Dakshayagna Veenasana) that narrates the destruction of Daksha’s sacrifice and the central drama leading to Shiva-Parvati narratives. The Kurma Purana also celebrates the Kashi Mahatmya, elaborating the sanctity of Varanasi, and records detailed descriptions of various tirthas (sacred waters) and kundas across the subcontinent. It speaks about varnashrama dharma—the duties appropriate to castes and life stages—and weaves together genealogies and royal lineages.

What is surprising to modern readers is the Kurma Purana’s philosophical breadth. It opens with prakriti-purusha tattva—the foundational thought of nature and consciousness interaction—and includes a systematic exposition of Samkhya darshana, the philosophical school that analyzes the universe through enumerated elements, senses, and the distinction between prakriti and purusha. At times it reads like a manual of cosmology and at other times like a devotional anthology celebrating Shiva and Devi: Shiva Mahima and Devi Mahatmya feature prominently.

There are also sections on Pashupada darshana (a Shaiva discipline and view), a detailed account of avatars, and a discourse on time. The Kurma Purana even enters into astronomical and calendrical calculation: divisions of time from minuscule fractions up to vast cosmic ages, showing the ancients’ desire to measure and master time through observation. Toward its later chapters the Purana discusses Kaliyuga Lakshanani—the characteristics of the Kali age—predicting an erosion of certain values and the shifts that define the era many of us live in today.

Kurma Purana predates Bhagavata Purana

One little-known fact I emphasize is that the Kurma Purana is older than the Bhagavata Purana in the literary strata. That means many seeds of later Bhagavata narratives are already present in Kurma. Recognizing this helps us to contextualize how narratives travel across Puranic literature—how motifs migrate and gain prominence in later texts. The Kurma Purana is not merely a sideline; it is a foundational compendium that shaped how subsequent texts constructed avatar lore and cosmological frameworks.

Language and choice of words: Janardhana becomes Kurma

When we read the slokas that describe the divine taking tortoise form, a single word choice opens up interpretative ground. Vyasa could have written that Vishnu or Narayana became Kurma. Instead he uses the word janardhana. One well-known verse runs:

Madhyasthane tadar tasmin kurma rupee janardhanaha

Janardhana is often translated as “the one who is for the people” or “the protector of people.” Vyasa’s choice conveys not just metaphysical fact but compassion: here the divine assumes the humblest possible shape—the tortoise that sits still under weight—to serve people. That humility is central to the Kurma message: a support that is invisible, patient, and unglamorous, but essential.

Reflect on that: we celebrate heroic feats and dramatic interventions. But who notices the foundation? What people rarely honor is the ark-like patient bearer that allows turmoil to be navigated. Janardhana as Kurma signals a theological emphasis: divinity is willing to take the unglamorous to sustain cosmic order—and does so out of service to people. It explains, in part, why Kurma attracted less public spectacle: its message is about endurance rather than heroic turbulence.

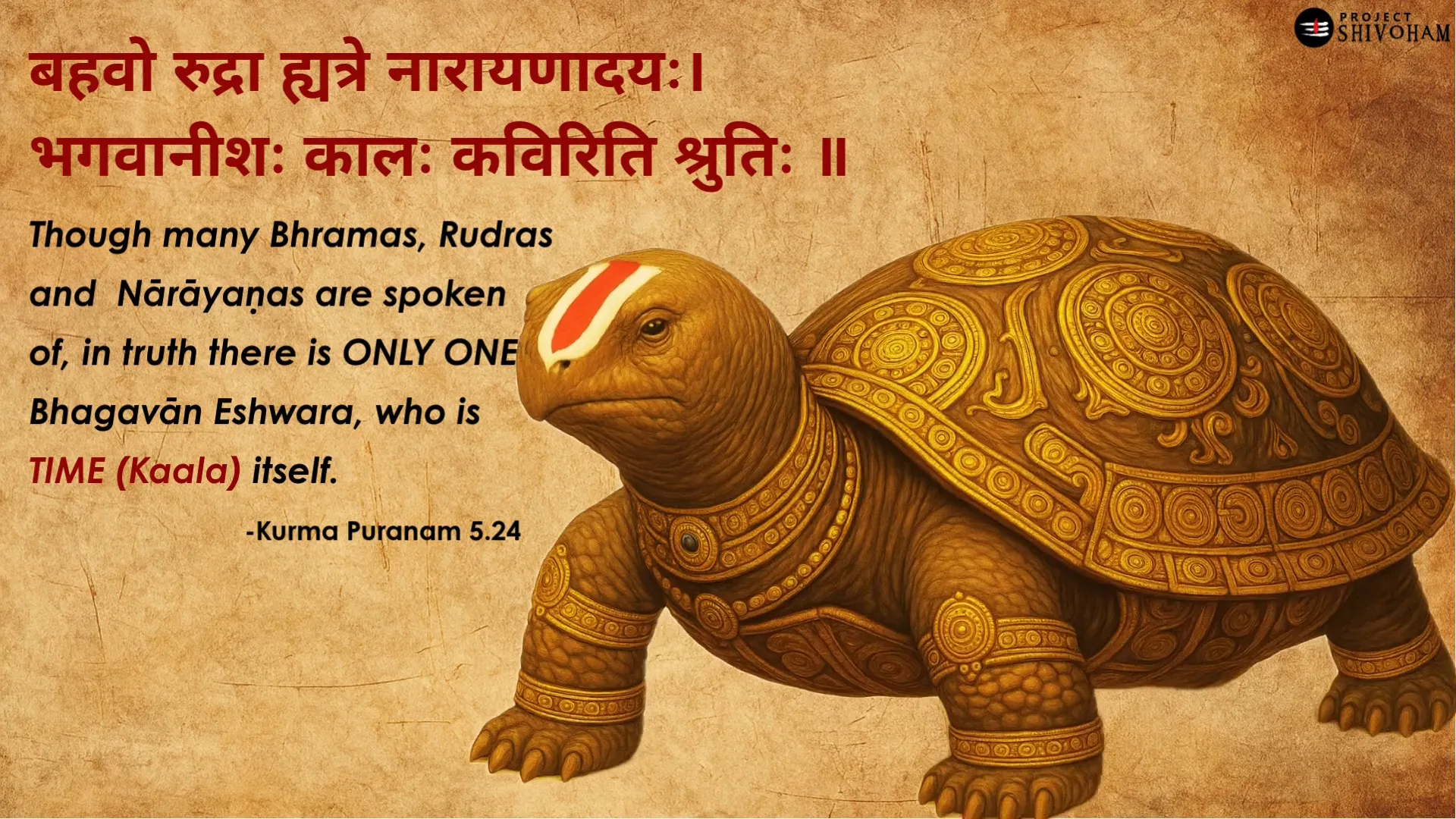

Kurma, time, and the philosophical center

Perhaps the most philosophically arresting statement in the Kurma Purana is a line that centers time itself as the ultimate lord. The Purana says—translated roughly—that though many Brahmas, many Rudras and many Narayanas are spoken of, in truth there is only one Bhagwan Ishvara, and that is kala—time itself. This is not an abstract aside; it locates the avataric activity within the machinery of time.

What does this mean practically? It means that all manifestations—gods, forms, temples—arise and pass within time’s flow. Time (Kala) is Mahakala, the ultimate reality that dissolves and reconstitutes everything. The Kurma Purana moves from bhakti-laden narratives to a stark, almost Stoic metaphysics: everything is transient; the support for existence is temporal structure.

This is consonant with the Bhagavad Gita’s own declaration where Krishna says, “I am Time” (aham kaalah). The Kurma Purana’s echo of that idea places Kurma within a philosophical frame: the tortoise is a temporal bearer. It supports the churning at a particular time and then dissolves into the larger temporal economy. If Kurma reminds devotees of patient endurance, the Purana reminds them of time’s sovereignty over all phenomena.

Cross-cultural resonances: Srid Paho and the Sri Chakra on the back of the tortoise

The idea of a tortoise as cosmic support is not unique to Vaishnavism. Across religious streams we find similar symbolic uses. In Tibetan Buddhist traditions there exists the motif of “srid paho” (also transliterated several ways), often depicted on copper plates, where a tortoise carries the mandala of existence on its back. This is not a borrowing of Hindu Kurma worship, nor does it imply Buddhists worship Vishnu as Kurma. Rather, it reveals a shared symbolic grammar: the tortoise as the steady, patient foundation of the cosmos.

Likewise, in the Shri Vidya tantric tradition the Sri Chakra (Sri Yantra)—a diagram considered a microcosm of the cosmos and an instrument of worship—is frequently carved on the back of a tortoise. Adi Shankaracharya himself consecrated Sri Yantras carved on tortoise bases, signaling the antiquity and orthodoxy of this practice. The tortoise here functions as a sacred pedestal that symbolizes stability and grounding for the most intricate metaphysical diagram humanity has devised.

These convergences—Vaishnava Kurma, Buddhist Srid Paho, Shri Vidya’s Sri Chakra—indicate a shared contemplative insight across traditions: the cosmos needs a patient, steady bearer. Different systems express the concept differently, but the continuity of the idea testifies to its intuitive resonance across the subcontinent and the Himalaya.

Why are there so few temples dedicated to Kurma?

This is the central question that motivated my research and my video. After visiting Srikurmam and studying the evidence, several interlocking reasons account for the modest cultic presence of Kurma in the temple world.

1. Kurma as foundation rather than heroic figure

Most cultic attention accrues to dramatic, interventionist deities—Rama, Krishna, Narasimha—whose narratives center heroic acts, direct engagement with devotees, and salvific episodes. Kurma’s role is essentially supportive and static: hold the weight, absorb the pressure, let the churning proceed. Narratively this does not lend itself to the ongoing ritual drama and emotional identification that animate public cults.

2. Iconography difficult for temple-theater

Kurma depictions are often integrated into larger scenes (Samudra Manthan) or appear as symbolic elements (tortoises carved at feet of goddesses) rather than as independent, anthropomorphic murti with which devotees can easily interact. The iconographic space for a full-scale, emotive deity is limited, making it harder for the avatar to become an independent cornerstone for temple festivals, kirtanas, or theatrical narratives that sustain mass devotion.

3. Temple politics and patronage

Many temples owe their scale and visibility to royal patronage. Kings tended to sponsor deities that conformed to public, monumental cults and political legitimations. Forms like Rama and Krishna were politically useful and theatrically potent. Kurma, being associated with foundational support, was less politically instrumentalized and therefore less likely to receive grand royal endowments. Consequently, fewer monumental temples were ever built specifically for Kurma.

4. Sectarian and iconographic consolidation

Over centuries, Vaishnavism crystallized around forms that were theologically and liturgically useful: Vishnu-Narayana, Venkateswara, Rama, Krishna. As sectarian lines hardened and invading forces targeted prominent shrines, peripheral forms were compressed or absorbed into more dominant schemas. Rare forms like Vaikuntha Kamalaja were often lost or disappeared into fragmentary museum collections. The consolidation of temple practice played a role in marginalizing Kurma as a primary object of worship.

5. The humble avatar resists spectacle

Kurma’s theological message—service, endurance, humbleness—resonates more in reflective metaphysical texts than in carnivalized public drama. Devotional cultures that emphasize spectacle naturally produced bigger cults around avatars with charismatic narrativity. Kurma’s quiet function and symbolic status meant that popular attention often overlooked the avatar even as his role remained indispensable.

What Srikurmam teaches us about tradition and survival

Srikurmam is far more than an archaeological curiosity. It demonstrates how traditions survive at the margins. In Srikurmam we see continuity in three domains:

- Ritual continuity: ongoing worship and festivals centered on Kurmanaatha Swami.

- Iconographic continuity: preservation of rare forms like Vishnu Durga and residual traces of Vaikuntha Kamalaja.

- Ecological continuity: the living tortoise population integrated with ritual practice.

These continuities matter because they preserve the form of devotion that might otherwise have been lost. Where grander temples attracted attention and often destruction, small sanctums like Srikurmam were hidden, preserved by local communities. Their marginality became their protection. The local people’s decision to hide the temple under sand and powder during times of danger was not an act of despair but of devotion: they chose concealment to ensure the avatar’s presence could endure. That act—hundreds of hands burying what they held dear—creates an ethic of participatory conservation that modern heritage preservationists often overlook.

Ritual life at Srikurmam: what to expect

When you visit living temple sites like Srikurmam, you are not visiting a museum. You enter a place where rituals are ongoing; where villagers perform rites related to birth, marriage, and death; where the temple pond is a locus for immersion rites that are otherwise rare in Vaishnava contexts; and where the ecology of tortoises is part of the ritual topography.

Daily pujA involves standard Vaishnava worship—arishtas, abhishekas, naivedyas—for the Kurma deity. But local adaptations make Srikurmam unique: funerary immersion at Shweta Kundam, a living memory of the king Shweta Chakravarti, and the continued recognition of a coupled deity structure where Durga and Vishnu exist in hybrid forms that challenge the rigid sectarian categories of later centuries.

Respect local customs: do not handle tortoises; approach ritual acts with humility; and if you are fortunate enough to visit during a festival, observe how processions navigate tight courtyards where the tortoise population is treated as living symbols rather than impediments to ritual movement. This is the kind of intimacy that larger, more tourist-oriented temples often lose.

Conserving the intangible: oral tradition, sthalapuranam, and living memory

One of the most fragile things is the memory itself. While stones can be buried and later revealed, stories can be lost in two or three generations. Srikurmam’s endurance owes much to oral tradition and the Sthala Purana preserved in texts like Padma Purana and in village recitation. Even the name Shweta Kundam—which ties to a king from Krityudha—demonstrates how place-name continuity can function as a mnemonic anchor. When landscape, language, and ritual tie together, tradition survives.

Oral narratives also explain why some iconographies persist in peripheral sites. When major cult centers were destroyed or reconfigured, local communities often retained older forms within home shrines and village temples. These practices are invisible to macro-historians because the records are local and the sites are small. Yet such local survival is crucial to understanding how traditions evolve rather than being obliterated in linear historical narratives.

Reflections on symbolism: foundations, humility, and public memory

Kurma teaches us something psychologically and culturally important. Civilizations valorize the visible and dramatic. Foundations get overlooked. In religious imagination, the tortoise is a reminder of the virtue of being the bearer. Kurma’s lack of public spectacle is not a failure; it is a teaching. A tradition that remembers Kurma is a tradition that recognizes the invisible work that sustains life, order, and ritual. This is a lesson in dharma: the morally important is sometimes unnoticed and yet indispensable.

When we walk past a temple and glance at the pedestal, look for little tortoises carved at goddess feet, and remember that even the Sri Yantra might be placed on a tortoise base—these are tiny signs of an ancient symbolic consensus across schools and regions. Ekam sat vipra bahudha vadanti—the one truth, called by many names. Kurma reminds us of the unity under difference and the quiet endurance that undergirds cosmic drama.

Conclusion: Reclaiming Kurma’s place in our religious imagination

Kurma avatar is not absent so much as hidden: hidden in plain sight across temple pedestals, in the anonymous potholes of village ponds, in a single swayambhu temple by the coast, and in the texts that predate the later popular retellings. To recover Kurma’s place in public memory is to honor foundations: the unseen, the patient, the supportive. It is also to remember that tradition survives in many ways—through stone and soil preservation; through oral recitation of sthalapuranas; through the ritual ecology of tortoise populations; and through the everyday acts of villagers who risked everything to hide what they loved.

If you are drawn to the Kurma story, consider visiting Srikurmam with humility and curiosity. Support local conservation efforts and listen to the elders. Read the Kurma Purana to understand the depth of its philosophy: the blend of Samkhya analyses, Shiva-Devi praise, astronomical calculation, and Kaliyuga diagnosis gives the text an integrative quality that broadens our understanding of how medieval authors framed cosmic history.

Above all, let Kurma teach us to honor foundations—in religion, culture, and life. The tortoise does not seek applause. It simply bears the load, steady and patient, as time itself moves everything along. In a world that constantly celebrates the visible, Kurma invites us to pay attention to the sustaining work that makes life possible.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: Why is Kurma always depicted as the second avatar?

A: Kurma’s placement in the Dashavatara sequence is narrative-structural: the second incarnation appears early in the cosmic tale of corrective intervention. The Samudra Manthan happens before many subsequent avataric missions (like Rama and Krishna), hence Kurma’s early placement. It reflects a cosmological chronology: the vessel-of-support role is foundational to the cycles of creation and subsequent avataric work.

Q: Are there other Kurma shrines besides Srikurmam?

A: Srikurmam is the only major, continuously worshipped temple in the world where Vishnu is the presiding deity in his Kurma form in a large living tradition. There are, however, smaller pedestals, carvings, and motifs across India—tortoise carvings at the feet of goddesses, Sri Yantras on tortoise bases, and Dashavatara panels that include Kurma. But none match Srikurmam’s unique combination of swayambhu status, Shweta Kundam rites, and ongoing living ritual dedicated specifically to Kurma.

Q: Is Kurma worship restricted to any particular sect?

A: Kurma is primarily within Vaishnava mythic space, but the avatar’s symbolism transcends strict sectarian boundaries. The Kurma Purana itself contains praises of Shiva and Devi and engages with Shaiva and Shakta ideas. At Srikurmam, the presence of Vishnu Durga and Vaikuntha Kamalaja demonstrates theological fluidity. Kurma’s symbolic scope—foundation, time, stability—makes the avatar a concept that invites cross-sectarian appropriation rather than narrow sectarian exclusivity.

Q: Why are tortoises found alive at the Srikurmam temple?

A: The living tortoise population at Srikurmam is both ecological and ritual. Historically, tortoises have been associated with sacred waters and temple ponds, and at Srikurmam they are given a degree of ritual respect. They are not captive animals but wild inhabitants of the pond and precincts. Their presence reinforces the sacred geography: a living embodiment of Kurma in the temple’s immediate experience.

Q: How does the Kurma Purana differ from other Puranas?

A: The Kurma Purana is distinctive for its breadth and integrative approach. It contains avatar narratives but also delves into Samkhya philosophical exegesis, devotional hymns to both Shiva and Devi, a Kashi Mahatmya, and extensive calendrical and astronomical material. It predates several later Purana layers and contains seeds of narratives that appear in the Bhagavata Purana. Its philosophical center—emphasizing time as the ultimate Ishvara—gives it a unique metaphysical posture among the Puranic corpus.

Q: Can Kurma symbolism be integrated into contemporary spiritual practice?

A: Yes. Kurma teaches patient endurance, quiet support, and humility. These are ethical and spiritual themes that transcend ritual specifics. Contemplative practices can cultivate Kurma-like steadiness: equanimity under pressure, silent service, and recognition of the invisible foundations of life. For temple-centered devotees, engaging with Srikurmam and reading the Kurma Purana provide traditional contexts for those teachings.

Q: How can one support preservation of sites like Srikurmam?

A: Support can take many forms: respectful pilgrimage that contributes to local economies, donations to temple trusts that maintain rituals and the pond ecology, volunteering with heritage groups that document Sthala Puranas and oral histories, and advocating for legal protections for small heritage sites. Importantly, conservation of living tradition requires supporting the communities who keep those traditions alive.

Q: Is there archaeological evidence for the antiquity of Srikurmam?

A: The sthalapuranic continuity, place names like Shweta Kundam, and stratigraphic traces in the architecture indicate great antiquity. The swayambhu claim places its origin in mythic time. Archaeological investigations, epigraphic records and temple architecture provide cross-lines of evidence for its long-standing presence, but like many sacred sites, the most reliable conservation mechanism has been living tradition rather than uninterrupted monumental patronage.

Q: What are some recommended readings to learn more?

A: Primary reading includes the Kurma Purana and the Samudra Manthan passages in broader Puranic literature (Vishnu Purana, Padma Purana, Bhagavata Purana). Scholarly studies on the Dashavatara iconography, research on temple survival strategies during medieval invasions, and ethnographic studies of Srikurmam and similar kshetras will add depth. Local Sthala Puranas and temple histories (often compiled by temple trusts or regional historians) are invaluable for contextual specifics.

Final thought

Kurma is a lesson in humility for individuals and for civilizational memory. Foundations rarely seek attention, yet civilization crumbles without them. To appreciate Kurma is to appreciate the quiet supports of life—the teachers who do not publish, the hands that bury what they love to save it, the ecosystems that sustain ritual life, and the texts that remind us of time’s supreme role. If you take anything from this article, let it be the value of noticing: look down at the pedestal, listen to the villagers, and read the old texts. There, you will meet the tortoise: steady, patient, quietly holding the cosmos for us.

With gratitude to the elders, scholars, and devotees who keep these memories alive, and thanks to Project Shivoham for inspiring this longer written reflection on a small but immensely significant avatar.

This article was created from the video Why no temples for Kurma Avatar? with the help of AI. Thanks to Aravind Markandeya, Project Shivoham.