India’s maritime history is a vast, fascinating tale that stretches back thousands of years, revealing a legacy of innovation, exploration, and cultural exchange that has shaped civilizations across the Indian Ocean and beyond. From ancient dugout canoes to sophisticated ocean-going vessels, India’s shipbuilding and navigation techniques were once among the most advanced in the world. Yet, much of this heritage has been forgotten or overshadowed by colonial narratives.

In this comprehensive exploration, we journey through India’s maritime past—examining archaeological evidence, ancient scriptures, indigenous shipbuilding technologies, notable maritime powers like the Cholas and Marathas, and the devastating impact of colonialism. Finally, we celebrate the revival of India’s shipbuilding tradition with the induction of the INSV Kaundinya, a stitched ship that reconnects modern India with its glorious nautical roots.

This article draws inspiration and insight from the detailed documentary created by Project Shivoham, which meticulously uncovers India’s lost maritime genius. Let us embark on this voyage through time and water to rediscover the forgotten history of Indian ships.

Table of Contents

- Outline

- Introduction to the Maritime Heritage of Humanity

- Archaeological Evidence of Ancient Indian Navigation

- Ancient Indian Scriptures on Shipbuilding and Navigation

- Indigenous Shipbuilding Technologies and Techniques

- India’s Maritime Powers in the Pre-Colonial Era

- India’s Maritime Trade and the Myth of Discovery

- Colonial Suppression and Decline of Indian Maritime Legacy

- The Revival: INSV Kaundinya and the Stitched Ship Tradition

- Understanding the Stitched Ship Technology

- FAQ: Common Questions on Indian Maritime History

- Conclusion: Reclaiming a Proud Maritime Heritage

Outline

- Introduction to the Maritime Heritage of Humanity

- Archaeological Evidence of Ancient Indian Navigation

- Ancient Indian Scriptures on Shipbuilding and Navigation

- Indigenous Shipbuilding Technologies and Techniques

- India’s Maritime Powers in the Pre-Colonial Era

- Colonial Suppression and Decline of Indian Maritime Legacy

- The Revival: INSV Kaundinya and the Stitched Ship Tradition

- FAQ: Common Questions on Indian Maritime History

- Conclusion: Reclaiming a Proud Maritime Heritage

Introduction to the Maritime Heritage of Humanity

Humanity’s relationship with water is ancient and profound. The oldest known boat in the world, the Passy Canoe, housed in the Drents Museum in the Netherlands, dates back more than ten thousand years to around 8040 BCE. This simple hollowed-out log is a testament to early human ingenuity, demonstrating that even in the Stone Age, our ancestors were navigating rivers and lakes—fishing, traveling, and exploring.

Ten thousand years may seem like a long time, but in the grand timeline of human civilization, it marks only the beginning of our journey on water. Across the globe, every culture developed its own maritime technologies—from Polynesian outrigger canoes to Viking longships, Egyptian reed boats to South American balsas. Each played a pivotal role in trade, travel, and survival, shaping civilizations profoundly through their mastery of watercraft.

India’s maritime history is no exception. Although it may not claim the title of the oldest or greatest maritime tradition, the facts reveal a rich, complex history of shipbuilding and navigation that deserves recognition and revival.

Archaeological Evidence of Ancient Indian Navigation

India’s archaeological record provides compelling evidence of ancient maritime activity, showcasing a tradition of watercraft and navigation that spans thousands of years.

One of the earliest finds is a dugout canoe excavated at Pattanam, Kerala, dated between 36 BCE and 24 AD. This canoe, meticulously hollowed out from a solid log, was primarily used for fishing and riverine transport, particularly in the backwaters and coastal inlets of Kerala, but also across broader regions of Bharat.

Though humble in design, these dugout canoes are powerful symbols of practical engineering, demonstrating how natural resources were skillfully transformed into vessels capable of navigating water. Importantly, this canoe is not the oldest evidence of navigation in India, but it is one of the earliest hard archaeological proofs.

More recently, excavations have uncovered the Karakarapalli boat in Kerala, dated to between 1200 and 1500 BCE. These boats were larger and designed for longer journeys, likely used for short-distance oceanic travel and trade, as well as river navigation.

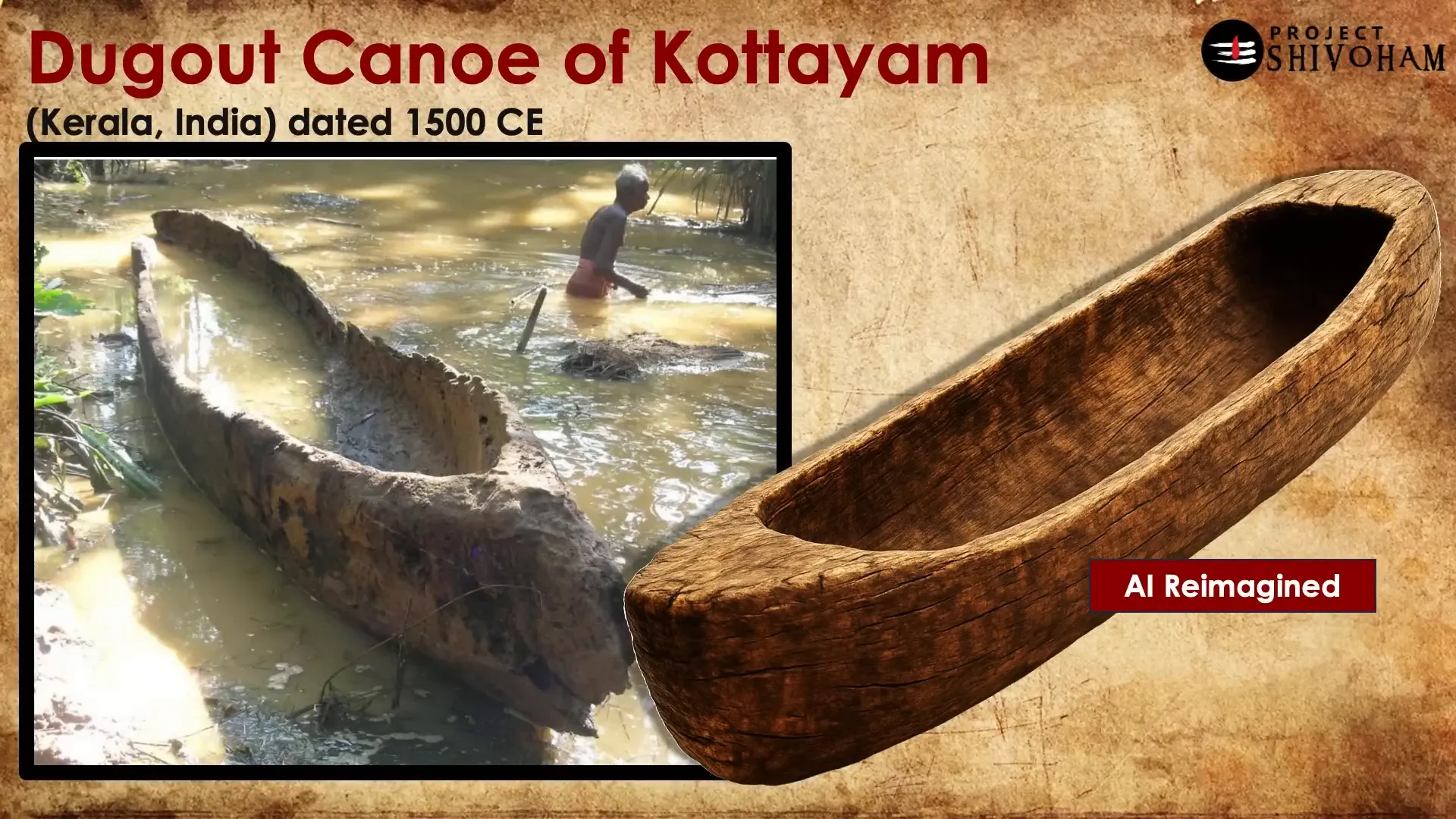

Another rare find is the fully intact dugout canoe from Kottayam, Kerala, dated to around 1500 CE. Similar to earlier canoes, it was primarily used for fishing and transportation in rivers and canals. Interestingly, the modern kayak design is inspired by such dugout canoes found worldwide.

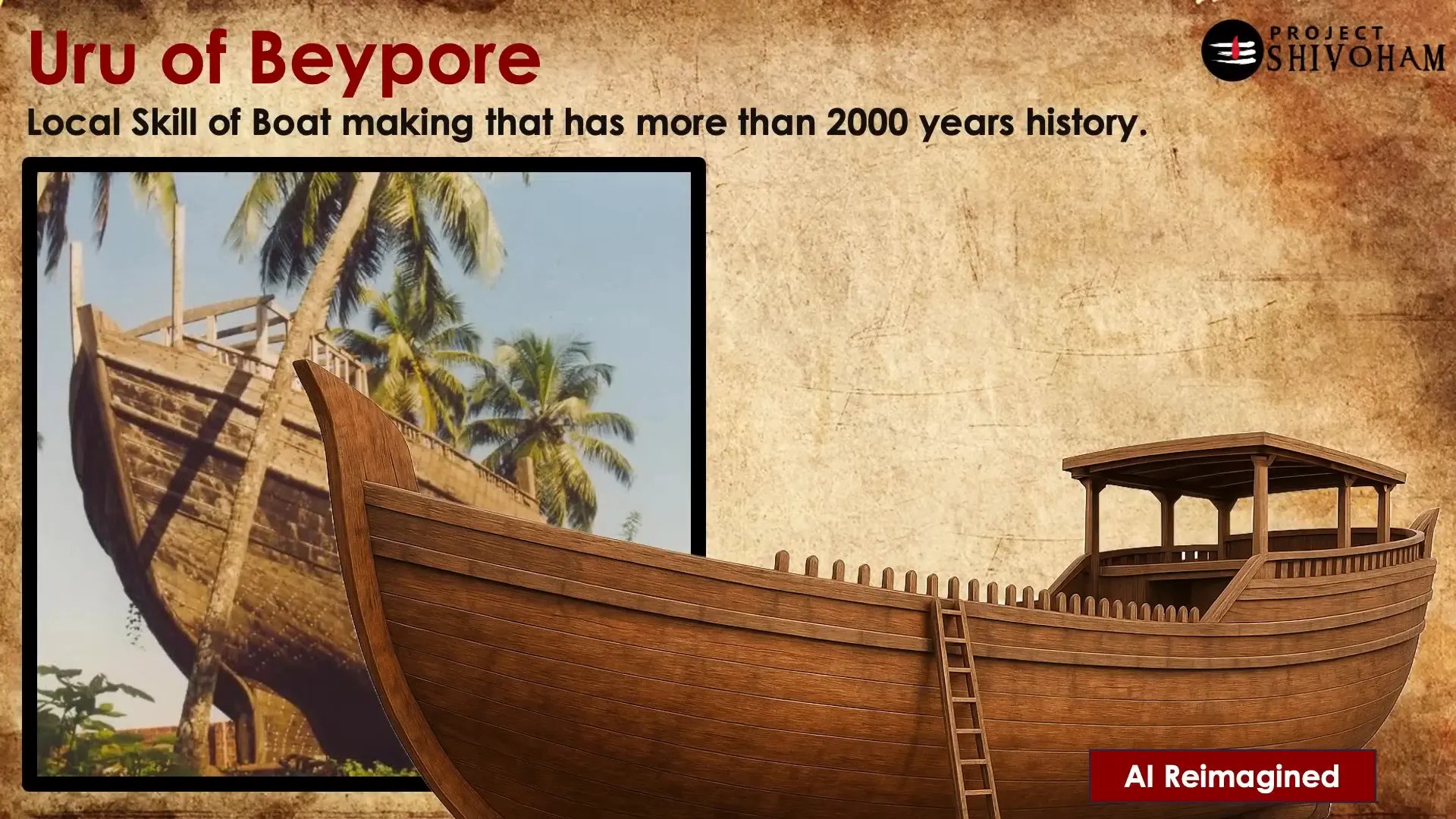

Beyond archaeological relics, living traditions such as the Urdu or fat boats of Beypore, Kerala, provide a remarkable link to the past. These boats have been hand-built for over 2,000 years using ancestral knowledge passed down through generations of master shipwrights, locally known as Kolas.

The Urdu boats were highly sought after by Arab traders for their strength, size, and seaworthiness, capable of carrying heavy cargo across the Arabian Sea. The continuity of this craftsmanship is extraordinary—a maritime heritage quietly thriving for millennia on India’s Malabar Coast.

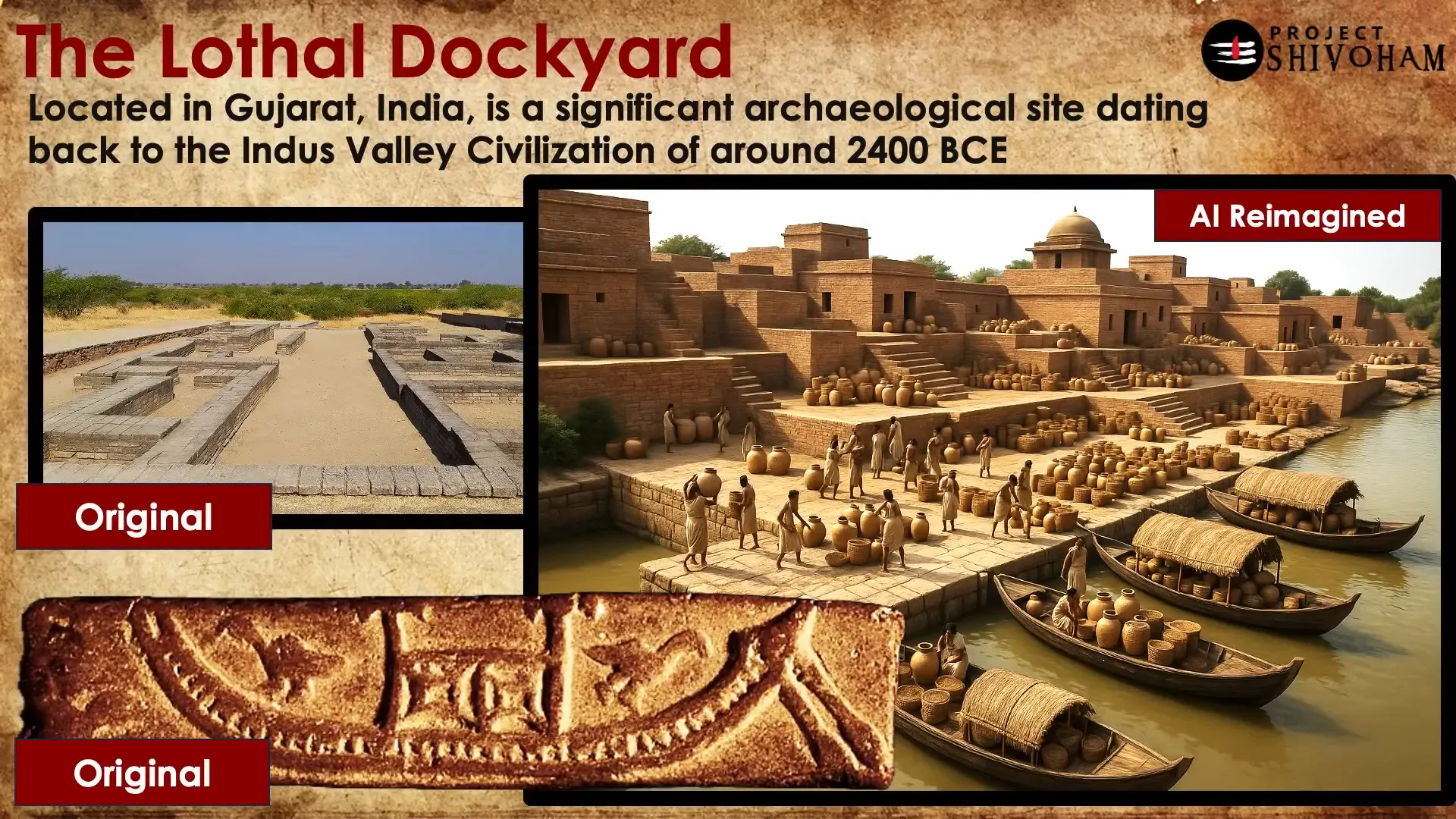

One of the most remarkable archaeological sites related to India’s maritime history is the Lothal Dockyard in Gujarat, dating back to around 2400 to 1900 BCE. Discovered in 1954, Lothal is considered the oldest tidal dockyard in the world. It was ingeniously designed with sluice gates, brick walls, and mooring platforms, connecting to a now-extinct tributary of the Sabarmati River to enable direct access to the sea.

Lothal was far more than a port; it was a major trade and industrial hub featuring bead-making workshops, warehouses, and a meticulously grid-planned town. This site illustrates India’s earliest evidence of organized maritime infrastructure, showcasing advanced knowledge of hydraulics, tidal flows, and engineering over 4,000 years ago.

Ancient Indian Scriptures on Shipbuilding and Navigation

While archaeology provides tangible proof, ancient Indian scriptures offer conceptual and technical insights into shipbuilding and navigation, revealing a sophisticated understanding encoded in texts spanning centuries.

These scriptures fall broadly into two categories:

- Scientific and Technological Texts: Detailed knowledge on ship design, construction, materials, navigation methods, and maritime regulations.

- Literary and Philosophical Works: Cultural, historical, and symbolic references showing how deeply maritime activity was woven into daily life and society.

Among the scientific texts, notable examples include:

- Yuktikalpataru: An encyclopedic text covering ship types, keel designs, star navigation, and crew roles.

- Samarangana Sutradhara: Discusses sacred geometry, materials, ship layouts, and vastu principles.

- Arthashastra: The ancient treatise on statecraft by Chanakya, which includes sections on naval ports, tolls, maritime customs, and regulations—remarkably detailing customs duties for imports and exports over 2,500 years ago.

- Brihat Samhita: Covers astrological timing, wind charts, and sea voyage planning.

- Kapal Satiram (Tamil Scripture): Focuses on ship construction techniques, wood selection, proportions, assembly, sailing mechanisms, and astro-navigation.

On the literary and philosophical side, texts such as the Rigveda, Sangam literature, Jataka tales, the Greek Periplus of the Erythrean Sea, Kalidasa’s Raghuvamsa, and others contain maritime references, underscoring the integral role of navigation in ancient Indian culture.

Focus on Kapal Satiram

Kapal Satiram, translating roughly to “Signs of Ships,” is an almost lost Tamil scripture that provides intricate details on shipbuilding. It covers:

- Structural framework: keel, central spine, ribs

- Wood selection guidelines for hull planks and mast bases

- Proportions and geometry: ratios for length, breadth, height, and angles

- Assembly and joinery techniques: joining ribs, clamps, binding strips

- Superstructure design: deck layout, mast, pillars

- Sailing and steering mechanisms, star navigation, mast mechanics, sail orientation

- Astro-engineering: selection of nakshatras and planetary positions for navigation

This scripture is estimated to be at least 1,000 years old, with practices documented in the Chola era, which dates back over 1,100 years.

Yuktikalpataru: The Encyclopedic Guide

Written by Raja Bhoj, Yuktikalpataru contains a dedicated section called Nava Vidya (knowledge of navigation). It covers:

- Classification of ships by size, deck structure, and purpose (riverine vs. oceanic)

- Principles of ship construction, dimensions, and structural components

- Guidelines for selecting and treating wood to ensure balance, geometry, and symmetry

- Navigation signs using stars and wind patterns

- Roles and responsibilities of crew members during the voyage

This comprehensive text illustrates the depth of maritime knowledge accumulated and systematized in India centuries ago.

Indigenous Shipbuilding Technologies and Techniques

India’s shipbuilding tradition was not just theoretical but deeply practical, with indigenous technologies honed over millennia to suit local geography and maritime conditions.

From ancient scriptures and surviving craft, we know that:

- Double-decked ships: Yuktikalpataru mentions large double-decked ships built with protective enclosures, indicating advanced structural design.

- Balance and weight distribution: Careful attention was paid to load distribution and symmetry in hull design to ensure seaworthiness.

- Wood treatment: Wood was soaked and treated with fish oil extracted from fish bones, an ingenious natural preservative that enhanced durability and flexibility.

- Navigation techniques: Wind patterns and star charts were used for route planning and steering.

One of the most remarkable indigenous technologies is the stitched ship, a vessel built without metal nails. Instead, wooden planks were stitched together using coir rope (coconut fiber) and sealed with natural resin. This technique made the hull flexible and resilient, ideal for the rough tropical seas of the Indian Ocean.

The stitched ship hull could absorb wave impacts, reducing damage, and required no dry docks for maintenance. Lightweight yet durable, these ships were a sustainable use of renewable materials and represent a unique civilizational knowledge almost lost to time.

Kathumaram: The Ancient Raft That Inspired Modern Catamarans

Kathumaram, dating back over 2,000 years, is one of the oldest surviving indigenous watercraft of South India, particularly along the Tamil Nadu coast. Mentioned in Sangam-era Tamil literature, Kathumaram is a raft made by binding three to seven buoyant wood logs with natural coir ropes.

Designed for coastal fishing and nearshore navigation, especially in shallow waters, Kathumaram’s flat, multi-log structure provided stability and maneuverability in rough seas. The term itself derives from Tamil: “Kathu” meaning “to tie” and “Maram” meaning “wood.”

This ancient design directly inspired the modern catamaran yacht, both in name and principle. European explorers encountered these stable, surf-resilient crafts along India’s coast, and Western naval designers later adapted the twin-hull structure for modern marine engineering.

Thus, the humble Kathumaram not only influenced naval architecture globally but also gave its name to one of today’s most popular and high-performance vessels.

India’s Maritime Powers in the Pre-Colonial Era

India’s maritime history is punctuated by powerful kingdoms and rulers who mastered the seas for trade, exploration, and military conquest.

The Chola Dynasty: Masters of the Ocean

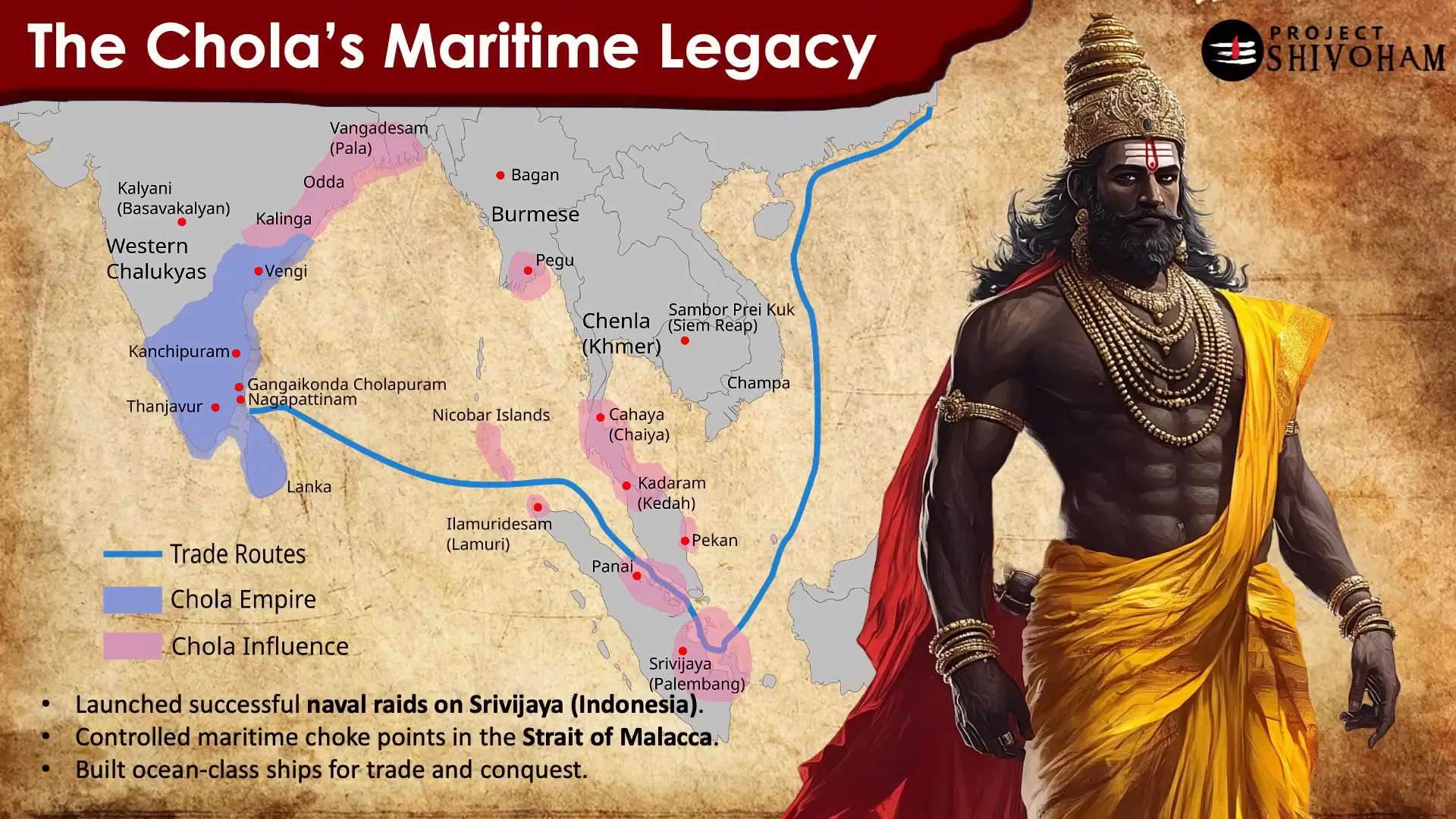

The Cholas, particularly under Rajaraja Chola I and his son Rajendra Chola I in the 10th and 11th centuries CE, were among India’s greatest maritime powers. They built ocean-class ships capable of sailing across the Bay of Bengal and beyond.

The Cholas maintained extensive trade routes with Southeast Asia, China, and the Arab world, trading textiles, spices, and precious goods. Their naval strength was not just commercial; it was also military. In 1025 CE, Rajendra Chola launched a massive naval expedition against the Srivijaya Empire (in modern-day Indonesia and Malaysia), successfully asserting dominance over key ports and controlling vital maritime chokepoints like the Strait of Malacca.

Two key centers of Chola maritime power were:

- Gangai Konta Cholapuram: The imperial capital built by Rajaraja Chola I after his victorious campaigns.

- Nagapattinam: A major port city and shipbuilding hub crucial for Chola maritime expeditions.

Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj: Early Modern Naval Strategist

Fast forward to the early modern period, Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj was the first Indian ruler in the last 500 years to institutionalize a naval force with strategic objectives. His navy defended the Konkan coastline, secured maritime trade routes, and resisted European naval powers.

Shivaji Maharaj established a robust network of coastal forts such as Sindhudurg, Vijaydurg, and Suvarnadurg and commissioned a fleet of indigenously designed ships for defense and rapid deployment.

In 2023, the Indian Navy updated its crest, replacing colonial-era symbols with elements from Shivaji Maharaj’s Raj Mudra, formally acknowledging India’s pre-colonial maritime tradition and reestablishing historical continuity.

The Ahom Kingdom’s Riverine Warfare

A lesser-known but powerful maritime story comes from the Ahom Kingdom in Assam. The Battle of Sarai Ghat in 1671 was a defining moment showcasing indigenous riverine warfare on the Brahmaputra River.

The Ahom navy used light, fast-moving boats adapted to the river’s reverse currents and narrow channels. Employing hit-and-run tactics, floating barriers, and ambush maneuvers, they offset the Mughal Empire’s numerical and artillery advantage. This home-ground mastery turned the Brahmaputra into a defensive ally, leading to a decisive Mughal retreat and securing Assam’s sovereignty for over a century.

Lachit Borphukan, the Ahom commander-in-chief, orchestrated a coordinated land and naval strategy that remains a powerful example of how localized maritime knowledge and leadership can overcome even mighty empires.

India’s Maritime Trade and the Myth of Discovery

India’s maritime legacy extends deeply into trade networks connecting the subcontinent with West Asia, East Africa, and Europe for over 2,000 years. One of the oldest evidences is the Roman map Tabula Peutingeriana, showing ancient trade routes and navigation paths.

Places in India such as Muchiri Pattanam (Muziris), Nagapattinam, and Vishakhapatnam have the suffix “Pattanam,” meaning “port” or “trade hub,” underscoring their long history as import-export centers.

The popular narrative that Vasco da Gama “discovered” the sea route to India in 1498 is a Eurocentric myth. Long before his arrival, the Indian Ocean trade network thrived, connecting East Africa, Arabia, India, and Southeast Asia through monsoon navigation.

Europeans sought a direct route to India to bypass Arabian middlemen who controlled trade and inflated prices. Vasco da Gama’s voyage around the Cape of Good Hope—the dangerous southern tip of Africa—was a monumental navigational feat, but it was enabled by local African and Arab pilots, especially from Malindi.

Far from the sanitized childhood stories, Vasco da Gama’s voyages were marked by brutality. In 1502, off the coast of Calicut, he captured a pilgrim ship returning from Mecca with over 300 Muslim men, women, and children, and ordered it looted and set ablaze with all passengers locked inside—a horrific act recorded in his own book, Landas de India.

This violent legacy contrasts sharply with the peaceful, thriving maritime culture that had existed in India and the Indian Ocean for centuries.

Colonial Suppression and Decline of Indian Maritime Legacy

India’s rich maritime tradition was systematically dismantled during British colonial rule. The British imposed restrictive laws like the Navigation Acts of 1838 and 1850, which crippled Indian shipyards, destroyed native navies, and barred indigenous ships from international trade.

Maritime castes, once respected shipbuilders and sailors, were reduced to mere laborers. Traditional knowledge was erased from education, and native engineering was delegitimized. The British monopolized ports and resources, reconstructing them to serve imperial interests.

This was not decline by accident but a deliberate design to maintain colonial dominance. India’s centuries-old oceanic power was replaced by dependency, and the indigenous maritime industry was all but erased.

The Revival: INSV Kaundinya and the Stitched Ship Tradition

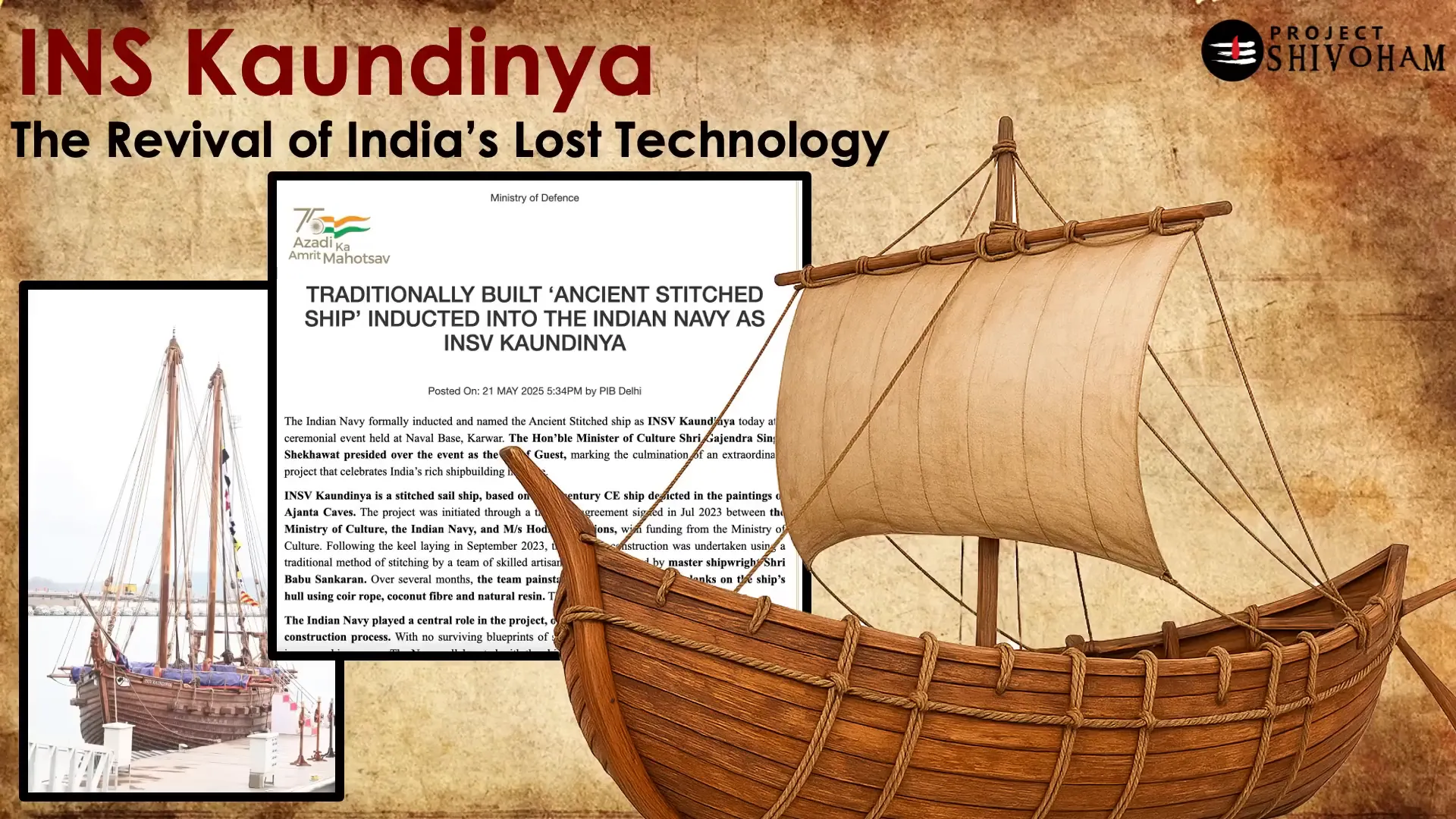

Amidst this history of loss and suppression, a remarkable revival is underway. On May 21, 2025, the Indian Navy inducted the Indian Naval Sailing Vessel (INSV) Kaundinya at the Karwar naval base in Karnataka. This vessel marks a significant resurgence of India’s ancient maritime heritage.

INSV Kaundinya is a recreation of a 5th-century CE stitched ship, inspired by the murals of the Ajanta Caves. It is constructed without metal nails; wooden planks are stitched together with coir rope and sealed with natural resin—a traditional technique practiced along India’s coastline for over 2,000 years.

Named after Kaundinya, a legendary Indian mariner who sailed across the Indian Ocean to Southeast Asia, the ship embodies India’s long-standing traditions of maritime exploration and cultural exchange.

The vessel features culturally significant elements, including sails decorated with motifs of the Ganda Berunda (a mythical two-headed bird) and the sun, a sculpted Simha Yali (mythical lion) on the bow, and a symbolic Harappan-style stone anchor on deck.

INSV Kaundinya is set to embark on a transoceanic voyage along ancient trade routes from Gujarat to Oman later this year, retracing historical maritime paths and demonstrating the seaworthiness of traditional Indian shipbuilding techniques that were lost over the last two to three centuries.

Understanding the Stitched Ship Technology

The stitched ship is a marvel of indigenous naval engineering. Unlike Western ships that rely on rigid iron nails and frames, these vessels use ropes to bind wooden planks. This construction provides flexibility, allowing the hull to absorb wave impacts—ideal for the tropical seas of the Indian Ocean.

They are lightweight, durable, and require no dry docks for maintenance, making them environmentally sustainable and cost-effective. This technique has been practiced for over 1,500 years, if not longer.

Kathumaram: The Foundation of Stitched Ships

The Kathumaram, as described earlier, is essentially a raft made by tying multiple wooden logs with coir ropes. It exemplifies the basic principle behind stitched ships: flexibility and stability through rope binding.

This design was scaled up in size and complexity to create the larger stitched ships like INSV Kaundinya, capable of oceanic voyages with robust hull frameworks and advanced sailing mechanisms.

FAQ: Common Questions on Indian Maritime History

Q1: What is the oldest evidence of navigation in India?

The oldest archaeological evidence includes dugout canoes from Kerala, such as the Pattanam canoe dated between 36 BCE and 24 AD, and the Karakarapalli boat from 1200 to 1500 BCE. Lothal dockyard in Gujarat, dating back over 4,000 years, shows advanced maritime infrastructure.

Q2: What were the main ancient Indian scriptures on shipbuilding?

Key texts include Yuktikalpataru, Samarangana Sutradhara, Arthashastra, Brihat Samhita, and Tamil scriptures like Kapal Satiram. These cover ship design, construction, navigation, and maritime regulations.

Q3: What is a stitched ship?

A stitched ship is a traditional Indian vessel constructed without metal nails. Wooden planks are stitched together with coir rope and sealed with natural resin, creating a flexible, durable hull suited for rough seas.

Q4: How did colonialism affect India’s maritime legacy?

British colonial rule systematically dismantled India’s shipbuilding industry through restrictive laws, economic sabotage, and cultural delegitimization, reducing indigenous shipbuilders to laborers and destroying native navies.

Q5: What is the significance of INSV Kaundinya?

INSV Kaundinya represents the revival of India’s ancient stitched shipbuilding tradition. It is a modern recreation of a 5th-century vessel, symbolizing a reconnection with India’s maritime heritage and showcasing indigenous naval technology.

Conclusion: Reclaiming a Proud Maritime Heritage

India’s maritime history is a story of brilliance, resilience, and innovation. From the earliest dugout canoes to the mighty ships of the Cholas, from the riverine navies of the Ahoms to the indigenously designed fleets of Shivaji Maharaj, India was once a dominant force on the seas.

The rich documentary and archaeological record, coupled with ancient scriptures, reveal a sophisticated and deeply rooted maritime culture. Unfortunately, colonialism disrupted this legacy, suppressing indigenous technologies and traditions.

However, the recent induction of INSV Kaundinya and the renewed interest in ancient shipbuilding techniques signal a hopeful revival. Reclaiming this heritage is not just about honoring the past—it is about inspiring future generations to appreciate and build upon the wisdom of their ancestors.

India’s journey on water is far from over. It continues, as vibrant and vital as ever, charting a course toward rediscovery and pride.

This article was created from the video The History of SHIPS with the help of AI. Thanks to Aravind Markandeya, Project Shivoham.