Skanda, also known by many names such as Kartikeya, Murugan, Subramanya, and Kumara, holds a significant place in the vast pantheon of Hindu deities. Revered as the god of war and victory, he is the son of Lord Shiva and Mahaparvathi and the brother of Lord Ganesha. While most people recognize Skanda primarily as a deity venerated in southern India—especially in Tamil Nadu, where he is affectionately called Murugan and considered the patron deity of Tamil culture and civilization—there is an expansive and fascinating chapter of Indian history that challenges this limited perception.

This article delves deep into the lost legacy of Skanda, tracing his worship and cultural significance not only in South India but across the entire Indian subcontinent and beyond—from Afghanistan and Nepal to Cambodia, China, and Japan. By the end, you will gain a fresh and comprehensive perspective on Skanda’s historical footprint, iconography, and spiritual importance that spans over two millennia. Let’s embark on this enlightening journey.

Table of Contents

- Understanding the Misconception: Skanda as a South Indian or Tamil God

- Skanda’s Origins in the Ramayana and Classical Sanskrit Literature

- Skanda in the Puranas: The Skanda Purana and Its Pan-Indian Reach

- The Six Abodes of Skanda: The Arupadai Vidu Temples of Tamil Nadu

- Iconography of Skanda: Symbols and Visual Cues

- Skanda Beyond Tamil Nadu: Ancient Statues and Artifacts Across Bharat and Asia

- The Royal Patronage of Skanda: Kings Named After the Deity

- Skanda’s Disappearance and Preservation: Historical Shifts in Worship

- Skanda in Buddhism: The Bodhisattva Protector

- Addressing Contemporary Misconceptions and Ideological Conflicts

- Summary: The Lost Legacy of Skanda Unveiled

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Understanding the Misconception: Skanda as a South Indian or Tamil God

One of the most popular yet fundamentally incorrect opinions about Skanda is that he is exclusively a South Indian god or primarily a god of the Tamil people. This notion is widespread but oversimplifies the rich and diverse history of Skanda’s worship that extends well beyond the southern states.

To clarify this misconception, we need to begin by exploring references to Skanda in ancient Indian scriptures, particularly the Vedas. Contrary to the idea that Skanda is a regional deity, he is mentioned in some of the oldest and most revered texts in Indian spiritual history.

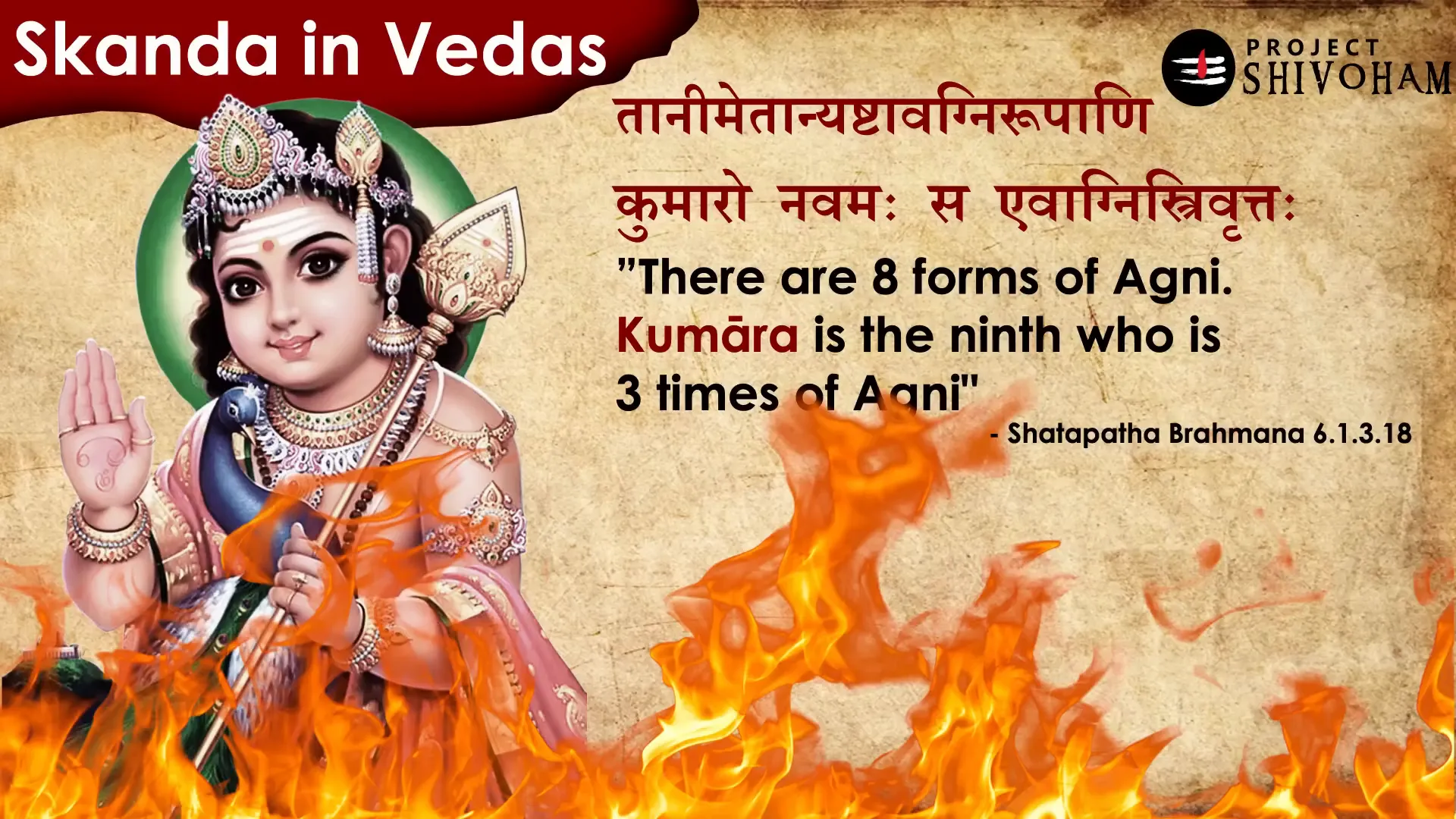

Skanda in the Vedas: Origins in Ancient Sanskrit Texts

The Shatapatha Brahmana, a prose text describing Vedic rituals and associated mythology, which is linked to the Yajurveda, explicitly mentions Skanda (referred to as Kumar). It states:

“There are eight forms of Agni, and Kumar, who is the son of Agni, is three times the power of Agni.”

Here, Kumar is not a generic or common name but a specific epithet for Kartikeya, revered as Agnibhu, meaning “the one born from fire.” This reference firmly roots Skanda in Vedic tradition, which predates many regional religious developments.

Besides the Shatapatha Brahmana, Skanda is mentioned in other key Sanskrit texts such as the Chandogya Upanishad and multiple Vedic hymns, underscoring his pan-Indian spiritual significance from ancient times.

Therefore, the idea that Skanda is a “South Indian god” is historically inaccurate. His worship and cultural importance are deeply embedded in the core of Indian civilization, transcending regional boundaries and linguistic communities.

The Central Role of Sanskrit (Samskritam) in Tamil Civilization

Addressing another prevalent but flawed narrative—particularly propagated by some Dravidian ideologues who diminish the role of Sanskrit in Tamil culture—it is essential to recognize that Sanskrit has been central to Tamil civilization’s spiritual and linguistic heritage. While Tamil is a language with a profound and ancient cultural legacy, Sanskrit’s influence is undeniable and foundational.

Many Tamil literary works, including Sangam literature, prominently feature figures and concepts rooted in Sanskritic tradition. Among these, Murugan (Skanda), Agastya Maharishi, and Shiva are pillars of Tamil spiritual identity. The origins of Murugan, in fact, trace back to Sanskrit texts like the Ramayana, further reinforcing the inseparability of Tamil and Sanskrit cultural streams.

Those who reject Sanskrit’s role in Tamil history often do so out of political or ideological motives rather than historical facts. The truth remains: Sanskrit and Tamil share a long, intertwined history that shaped the spiritual and cultural landscape of South India.

Skanda’s Origins in the Ramayana and Classical Sanskrit Literature

The Ramayana, one of the two great epics of India composed in Sanskrit by Valmiki Maharshi, contains references to Skanda that further emphasize his pan-Indian stature. Vishwamitra Maharishi narrates the origins of Skanda to Rama and Lakshmana in the epic:

“Skanda ityud bruvandeva, skandam garbha parishrvaat” (Translation: Vishwamitra Maharishi narrated to Rama and Lakshmana the birth and origins of Skanda or Kumar.)

This passage highlights that Skanda’s story is deeply embedded in the Sanskritic epic tradition, which has influenced Indian culture across all regions, including Tamil Nadu.

Moreover, the celebrated poet Kalidasa’s magnum opus, Kumarasambhavam, draws inspiration from the Ramayana. The very name “Kumarasambhavam” (the birth of Kumar) and the narrative of Skanda’s birth are rooted in these classical Sanskrit texts. Kalidasa’s work, written around the 5th century CE, remains a cornerstone of Indian classical literature and reinforces Skanda’s significance in the broader Indian cultural context.

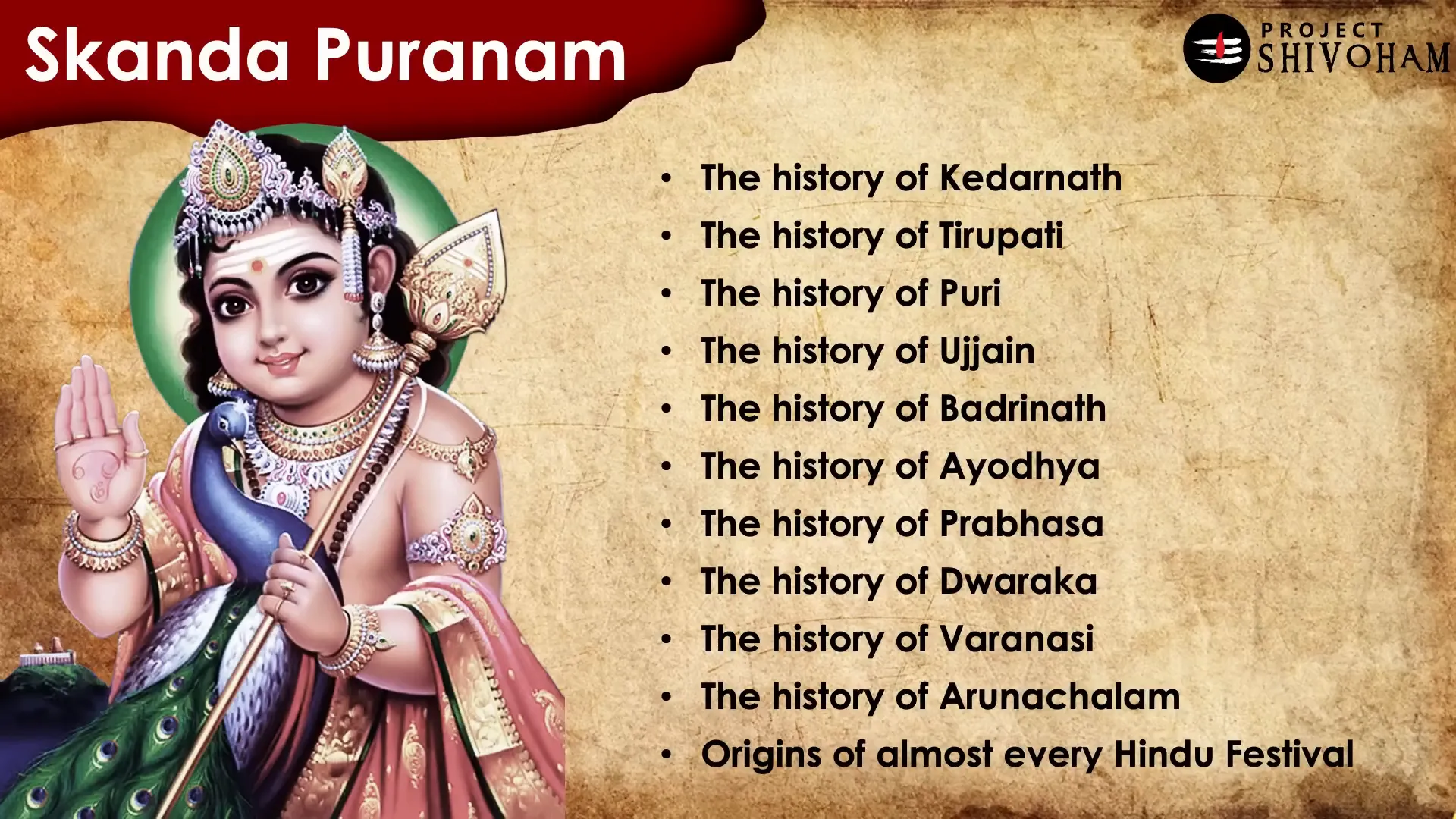

Skanda in the Puranas: The Skanda Purana and Its Pan-Indian Reach

The Skanda Purana is the largest of all Puranic texts, dedicated entirely to the history, mythology, and worship of Skanda (Kartikeya). It provides detailed accounts of various sacred sites (tirthas) and temples across Bharat (India), including locations as diverse as Kedarnath, Tirupati, Puri, Ujjain, Badrinath, and Ayodhya.

One particularly important historical fact documented in the Skanda Purana is the mention of Ram Janmabhoomi (birthplace of Lord Rama) in Ayodhya. The term “Ram Janmabhoomi” itself is derived from this Purana, and it has been cited extensively in legal judgments concerning the Ayodhya dispute. The Skanda Purana is referenced at least eighteen times in judicial proceedings to establish the existence of this sacred site.

Beyond Ayodhya, the Skanda Purana also narrates histories of other significant pilgrimage centers such as Prabhasa, Dwaraka, Varanasi, and Arunachalam. It is the origin of many major Hindu festivals including Diwali and Ram Navami, highlighting Skanda’s central role in shaping the religious and cultural fabric of Bharat.

Thus, Skanda is not merely a regional deity but a cosmic figure central to Sanatana Dharma and Indian cultural identity.

The Six Abodes of Skanda: The Arupadai Vidu Temples of Tamil Nadu

While the worship of Skanda is pan-Indian, it is true that the most vibrant and continuous tradition of his veneration exists in Tamil Nadu. The six most important shrines of Kartikeya in Tamil Nadu are collectively known as the Arupadai Vidu (meaning “six battle camps” or “six abodes”). These temples are:

- Tirupthani

- Palamudir Cholai

- Tirupchandur

- Swamimalai

- Palani

- Tirupanakkundram

These temples form the heart of Murugan worship and Tamil devotional culture. The question arises: why is Skanda predominantly worshipped in Tamil Nadu today, despite his widespread historical significance?

The answer partly lies in historical disruptions, including invasions and socio-political changes, which led to the decline of many Skanda shrines outside the south. Yet, Tamil Nadu preserved and nurtured the worship of Murugan with unmatched devotion, making it the cultural epicenter of Skanda’s legacy.

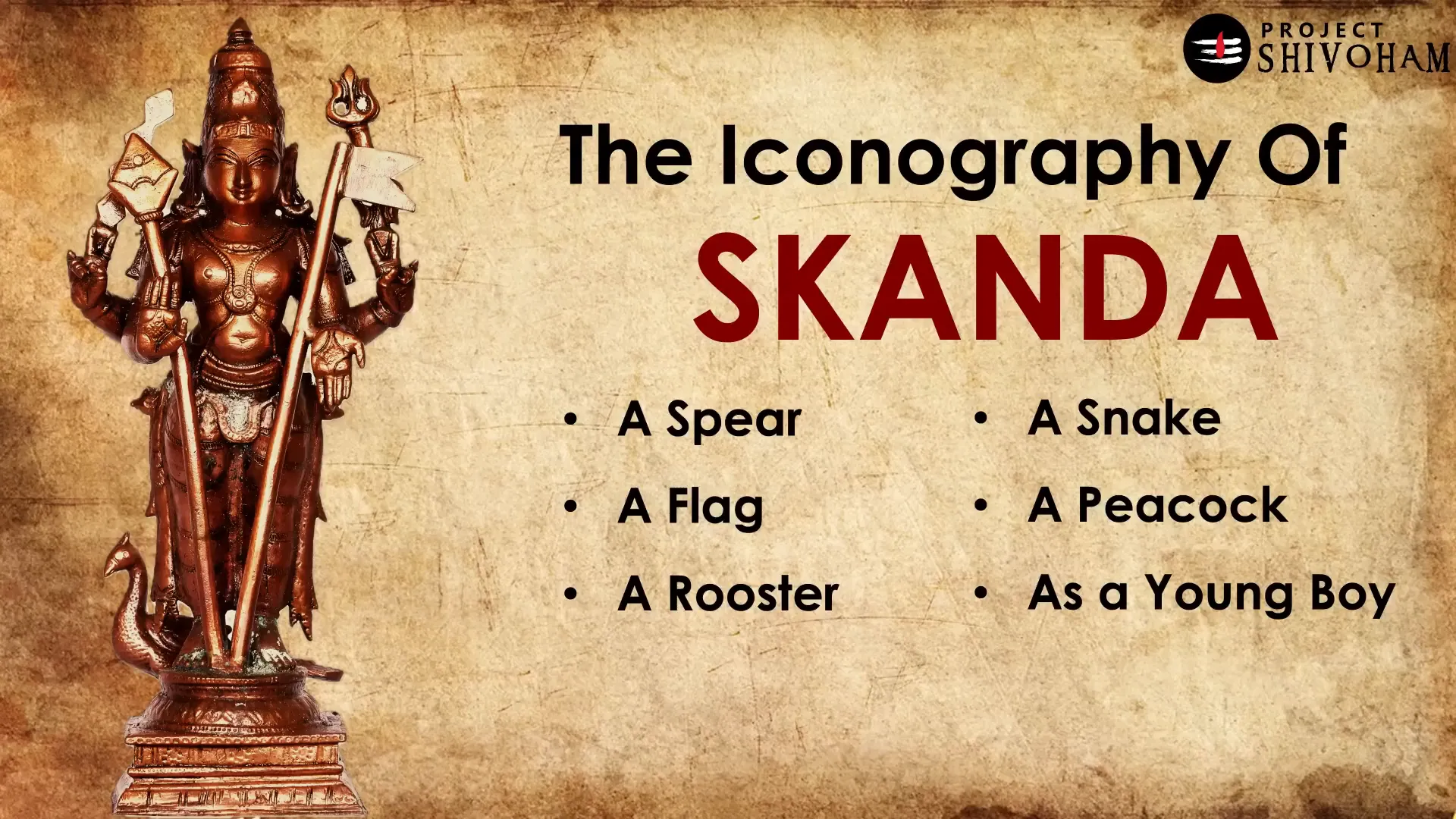

Iconography of Skanda: Symbols and Visual Cues

Understanding the iconography of Skanda is crucial to recognizing his depictions across various regions and time periods. Skanda is traditionally portrayed with six distinct visual symbols:

- Spear (Vel): His primary weapon, symbolizing valor and divine power.

- Flag: Often featuring a rooster emblem.

- Rooster: Symbolizing victory and the dawn.

- Snake: Sometimes depicted wrapped around or near him, symbolizing energy and protection.

- Peacock: His vahana (mount), representing beauty and strength.

- Youthful Appearance: Skanda is almost always depicted as a young boy or youthful warrior.

These six cues help identify Skanda in sculptures, paintings, and murals, even when the cultural or geographic context differs.

Skanda Beyond Tamil Nadu: Ancient Statues and Artifacts Across Bharat and Asia

One of the most compelling revelations in Skanda’s history is the discovery of numerous ancient statues and artifacts depicting him across a vast geographic expanse, from Nepal and Uttar Pradesh to Cambodia and Pakistan. These artifacts, housed in museums worldwide, testify to Skanda’s widespread worship over the last two thousand years.

Skanda Statues in Nepal and Southeast Asia

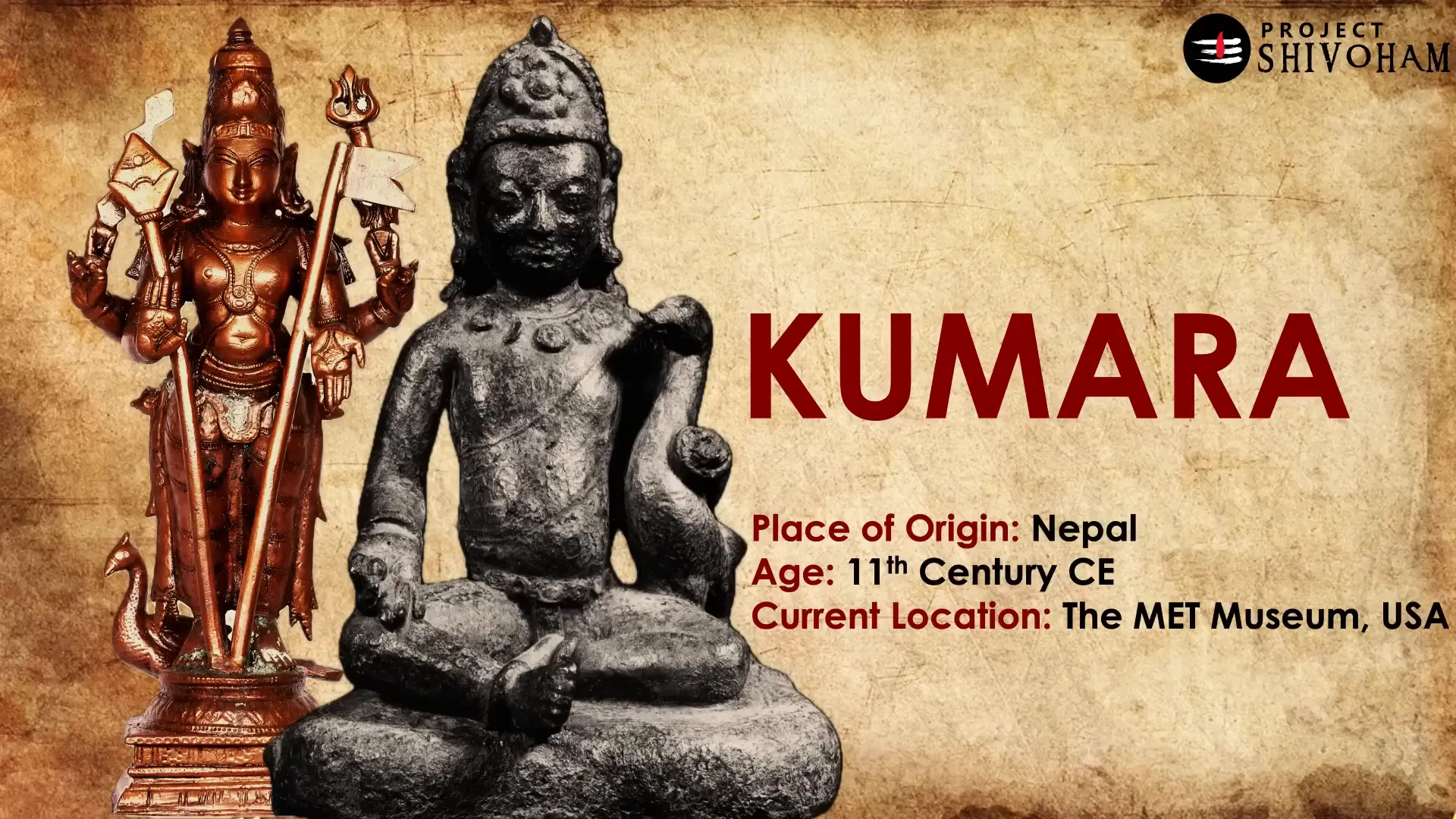

Several statues originating from Nepal, dating from the 11th to 18th centuries CE, depict Skanda as a young boy with his peacock vahana. These statues are currently housed in prominent museums such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art (USA) and the National Museum of Nepal.

Similarly, Cambodia, a Southeast Asian country with a rich Hindu-Buddhist heritage, has ancient Skanda statues dating back to the 6th to 10th centuries CE. One notable statue depicts Shiva playing with Skanda as a toddler, highlighting the continuity of the deity’s worship in these regions.

Skanda Statues from the Hindi Heartland and the Gupta Era

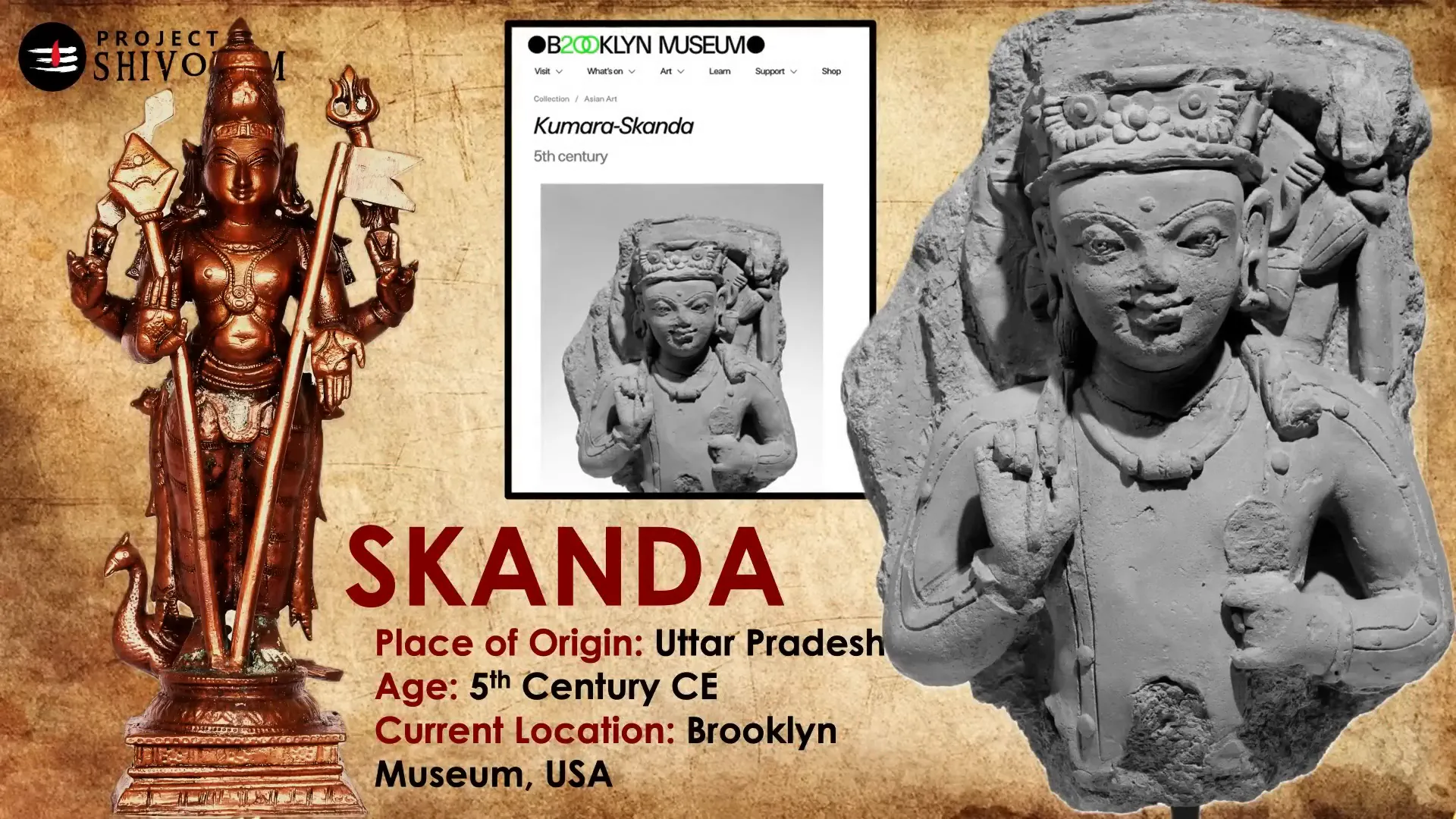

Moving northward, ancient statues from Uttar Pradesh, dating back to the 5th to 8th centuries CE, depict Skanda in various forms, often seated on a peacock and holding the spear (vel). Many of these artifacts belong to the Gupta dynasty era, a golden age of Indian culture and art.

One particularly important statue, housed in the Brooklyn Museum (USA), originates from Uttar Pradesh and dates back to the 5th century CE. Although the iconography is somewhat eroded, it is identified as Kumaraskanda, affirming Skanda’s presence in northern India during the Gupta period.

Skanda in the Gandharan Context: The Scythian Connection

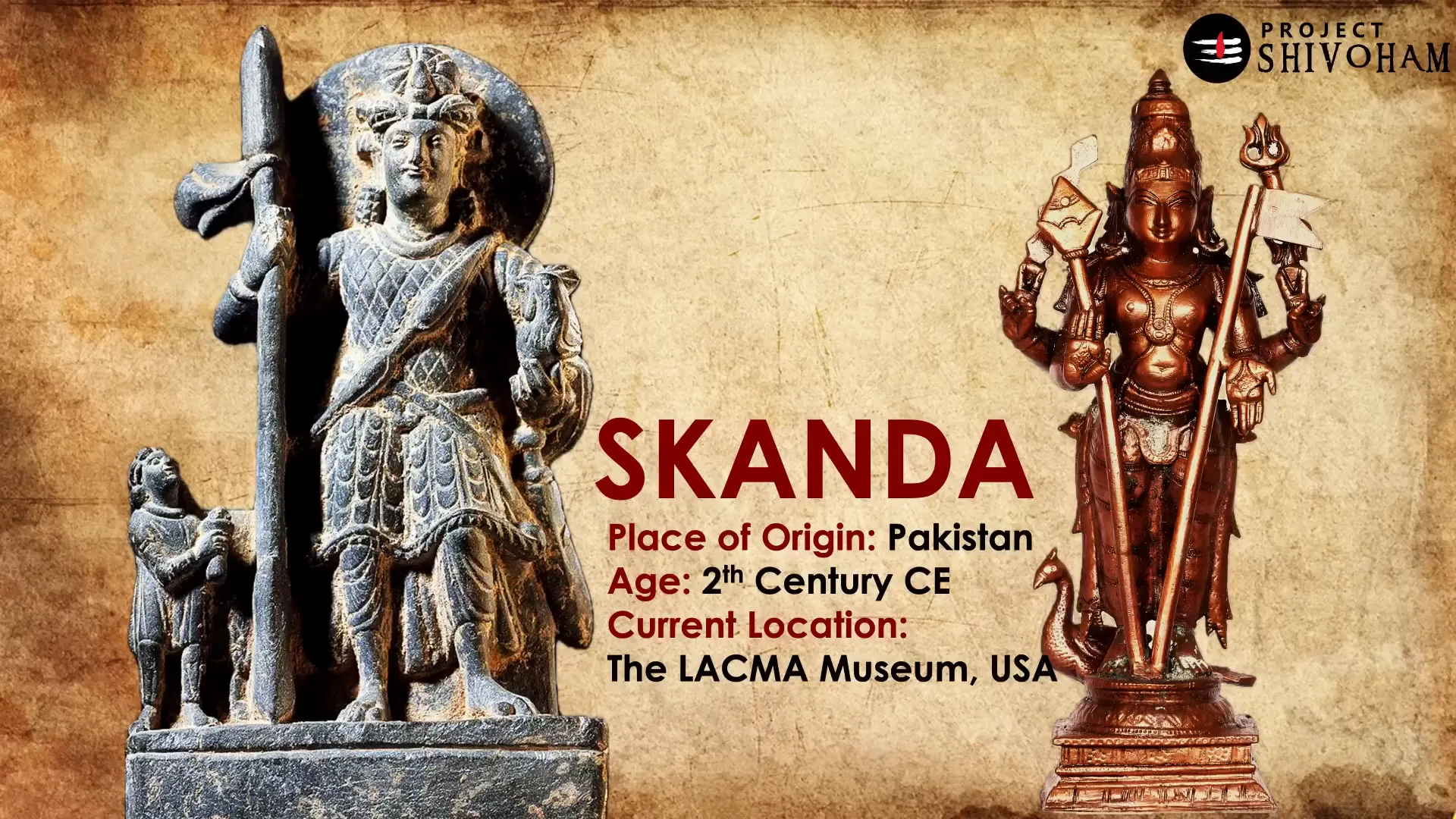

Among the most fascinating Skanda statues is one from the Gandharan region, covering parts of present-day Pakistan and Afghanistan, dating back almost 2000 years. This statue is currently in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) and depicts Skanda in a uniquely martial fashion.

Unlike the typical South Indian depiction of Skanda in a dhoti, this statue shows him wearing scaled armor reminiscent of the war attire of the Scythians—an ancient nomadic people who lived in the Eurasian steppes from the 7th to 3rd centuries BCE.

Skanda holds the spear (vel) in his right hand and a rooster in his left, consistent with his iconography. This representation reflects the Indo-Scythian cultural fusion, where Skanda was revered as a god of war by these polytheistic nomads who adopted several Hindu deities.

This statue is a powerful testament to the fact that Skanda’s worship was not confined to South India but was widespread across Northern and Central Asia.

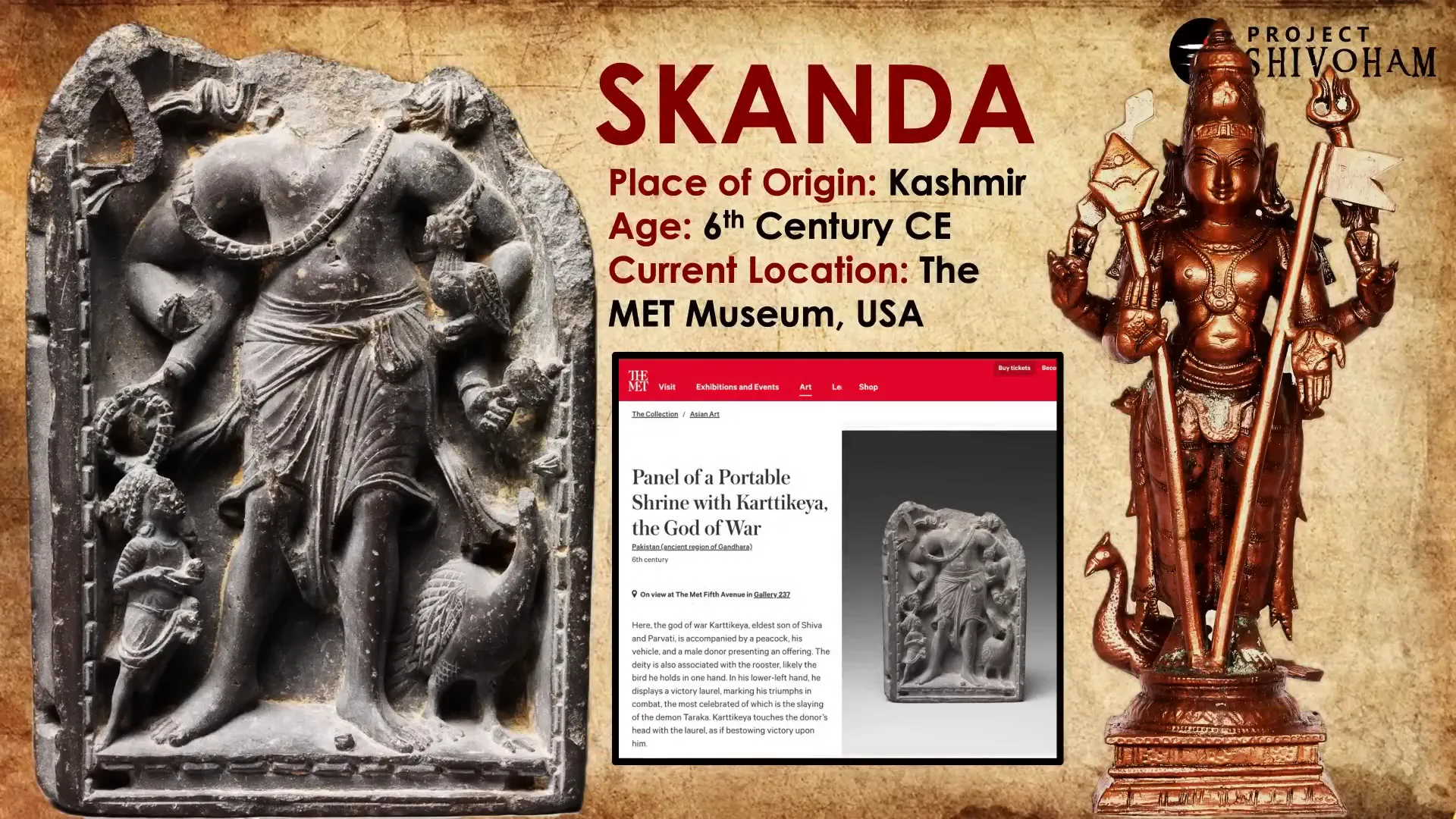

Skanda in Kashmir and Other Northern Regions

Further north, Skanda’s presence is evidenced by statues from Kashmir dating back to the 6th century CE. These statues, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, clearly show Skanda standing on a peacock, although some parts like the peacock’s head have been damaged—likely due to historical iconoclasm.

The existence of Skanda worship in Kashmir, a region far from Tamil Nadu, underscores the pan-Indian nature of his cult.

The Royal Patronage of Skanda: Kings Named After the Deity

The reverence for Skanda extended beyond religious worship into royal patronage. Several ancient Indian kings adopted names honoring Skanda, such as Kumaragupta and Skandagupta, rulers of the Gupta dynasty.

Coins from Kumaragupta’s reign depict Skanda prominently, showing him with his iconic peacock and spear. This royal association further highlights the deity’s importance in the political and cultural spheres of ancient India.

Skanda’s Disappearance and Preservation: Historical Shifts in Worship

Despite this rich and widespread heritage, the worship of Skanda experienced a decline in many parts of North and Central India over the past 500 to 1000 years. Various factors such as invasions, political upheavals, and cultural shifts contributed to this decline. The Islamic invasions, though responsible for the destruction of many temples, cannot be solely blamed for Skanda’s disappearance as other temples and cults revived over time.

However, the Skanda tradition survived and thrived in Tamil Nadu and parts of Southern India, where it remains the heart and soul of the regional culture. In Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, Skanda is also worshipped as Subrahmanya, with many temples dedicated to him.

This preservation of Skanda worship in the south is a cultural treasure, and while Tamil Nadu deserves respect for maintaining this legacy, it is important to acknowledge that Skanda’s roots and influence are far more extensive.

Skanda in Buddhism: The Bodhisattva Protector

Skanda’s influence is not limited to Hinduism. In Mahayana Buddhism, particularly in China and Japan, Skanda is revered as Bodhisattva Skanda, a divine protector of the Buddha’s teachings (Dharma).

Known as Vetuo in China and Idaten in Japan, Skanda is depicted as a heavenly general guarding Buddhist monasteries, stupas, and monks from harm. This role as a Dharma protector shows how Skanda’s identity transcended religious boundaries and was absorbed into other spiritual traditions.

Statues and images of Bodhisattva Skanda, dating back around 450 years, are housed in museums like the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Temples such as the Bowing Temple and Lingshan Temple in China continue to honor him as a guardian deity.

Addressing Contemporary Misconceptions and Ideological Conflicts

Unfortunately, contemporary ideological conflicts sometimes distort historical and cultural facts. Certain Dravidian ideologues who disparage Sanskrit (Samskritam) and claim Tamil as the sole ancient and pure language often ignore or deny the Sanskritic origins of many Tamil cultural elements, including the worship of Murugan.

These narratives, driven by political motives, overlook the deep interconnectedness of Indian languages and cultures. The fact that the oldest surviving statues of Murugan are found in regions like Afghanistan and Iran should be a testament to the pan-Indian and even transregional nature of this deity, rather than a reason to brand him as foreign or outsider.

Respect for all linguistic and cultural traditions is essential. Denigrating any one tradition undermines the unity and richness of India’s spiritual heritage. Skanda’s legacy, spanning multiple regions, languages, and even religions, exemplifies the pluralistic spirit of Indian civilization.

Summary: The Lost Legacy of Skanda Unveiled

To summarize the key points:

- Skanda, also known as Kartikeya, Murugan, Subramanya, and Kumara, is a pan-Indian deity deeply rooted in ancient Vedic and Sanskritic traditions.

- He is not exclusively a South Indian or Tamil god; his worship historically spanned from Afghanistan and Pakistan through Northern India to Southeast Asia.

- Ancient texts like the Ramayana, Skanda Purana, and classical Sanskrit literature document his origins and significance.

- Six major temples in Tamil Nadu (Arupadai Vidu) preserve his worship vibrantly today, but this is part of a much broader historical tradition.

- Skanda’s iconography includes the spear (vel), rooster, snake, peacock, and youthful form, which help identify him in sculptures and art across regions.

- Ancient statues from Nepal, Cambodia, Uttar Pradesh, Kashmir, and Gandharan regions attest to his widespread veneration over 2,000 years.

- Skanda was revered by Indo-Scythians and depicted in Scythian warrior attire, showing cultural syncretism.

- He was adopted into Mahayana Buddhism as Bodhisattva Skanda, protector of the Dharma in China and Japan.

- Royal patronage by kings like Kumaragupta and Skandagupta highlights his political and cultural importance.

- Modern ideological disputes sometimes obscure these facts, but the historical record is clear about Skanda’s extensive legacy.

Understanding Skanda’s lost legacy enriches our appreciation of Indian history, culture, and spirituality. It reminds us that Indian civilization has always been a tapestry of diverse yet interconnected traditions, united by shared reverence for deities like Skanda, whose influence transcended geography and time.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Who is Skanda, and why is he important in Hinduism?

Skanda, also known as Kartikeya, Murugan, Subramanya, and Kumara, is the god of war and victory in Hinduism. He is the son of Lord Shiva and Parvati and is revered as a divine commander of the gods. His worship symbolizes valor, protection, and triumph over evil.

Is Skanda only worshipped in South India?

No, while Skanda (Murugan) is especially popular in Tamil Nadu and parts of Southern India, historical evidence shows that his worship was widespread across the Indian subcontinent and even beyond, including regions like Nepal, Kashmir, Afghanistan, and Southeast Asia.

What are the key symbols associated with Skanda?

Skanda is typically depicted with six main symbols: the spear (vel), a flag, a rooster, a snake, a peacock (his mount), and a youthful form. These help identify him in various artworks and sculptures.

What is the significance of the Skanda Purana?

The Skanda Purana is the largest Puranic text dedicated to Skanda. It narrates his mythology and the history of many sacred sites across India. It also serves as a source for many Hindu festivals and rituals.

How is Skanda connected to Buddhism?

In Mahayana Buddhism, Skanda is revered as Bodhisattva Skanda, a divine protector of Buddhist teachings and monasteries. Known as Vetuo in China and Idaten in Japan, he is depicted as a heavenly guardian who safeguards the Dharma.

Why did Skanda worship decline in northern India?

Historical invasions, cultural shifts, and political changes led to the decline of Skanda worship in northern India. However, his worship survived robustly in Tamil Nadu and parts of southern India.

Are there ancient statues of Skanda outside India?

Yes, ancient statues of Skanda have been found in Nepal, Cambodia, and regions of present-day Pakistan and Afghanistan. These artifacts date back over a thousand years and are housed in museums worldwide.

What is the relationship between Sanskrit and Tamil in the context of Skanda?

Sanskrit and Tamil have a shared cultural and spiritual heritage. Skanda’s origins are documented in Sanskrit texts like the Ramayana and Vedas, which have influenced Tamil literature and religious practices. Both languages have contributed to the rich tapestry of Indian civilization.

Who were the Scythians, and what is their connection to Skanda?

The Scythians were ancient nomadic peoples from the Eurasian steppes. Indo-Scythians adopted Hindu deities including Skanda, whom they revered as a god of war. Skanda statues from the Gandharan region show him in Scythian warrior attire.

How can we respect the diverse traditions related to Skanda today?

Recognizing the historical and cultural diversity of Skanda’s worship encourages respect for all Indian traditions and religions. Avoiding ideological biases and embracing pluralism helps honor the unity and richness of India’s spiritual heritage.

This article was created from the video The Lost Legacy of SKANDA with the help of AI. Thanks to Aravind Markandeya, Project Shivoham.