Across the vast and intricate tapestry of ancient Indo-European civilizations, one divine figure emerges repeatedly — the supreme sky god, the celestial patriarch, the thunder wielder. Known by many names across different cultures and epochs, this deity connects the spiritual heritage of ancient Greece, Rome, the Balkans, the Baltic region, and India in a fascinating shared memory. In this exploration, we delve deep into the origins, transformations, and enduring legacy of this sky deity, tracing his journey from the Mycenaean clay tablets to the epic narratives of the Mahabharata.

This article draws inspiration from the insightful research and narration by Project Shivoham, who masterfully unpacks the layers of history, mythology, and Vedic philosophy to reveal the profound connections between Bhishma Acharya — a pivotal figure in Indian tradition — and the sky gods worshipped throughout ancient Europe. Join me as we unravel the story of why Bhishma was worshipped in Europe, and why the sky father’s archetype continues to resonate across continents even today.

Table of Contents

- The Ancient Sky Deity: Origins in the Mycenaean Civilization

- Zeus: The Supreme Sky God of Early Greece

- Jupiter: The Roman Transformation of Zeus

- Deipateros and Dheavas: Sky Gods of the Balkans and Baltic Regions

- The Common Thread: Dyauspater Across India and Europe

- Understanding Pitru Devata: Ancestor Veneration and Vedic Deities

- Dyauspater and Bhishma Acharya: The Mahabharata Connection

- Dispelling Myths: Aryan-Dravidian Theory and Cultural Continuity

- The Enduring Legacy of the Sky Father Across Continents

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

- Final Thoughts

The Ancient Sky Deity: Origins in the Mycenaean Civilization

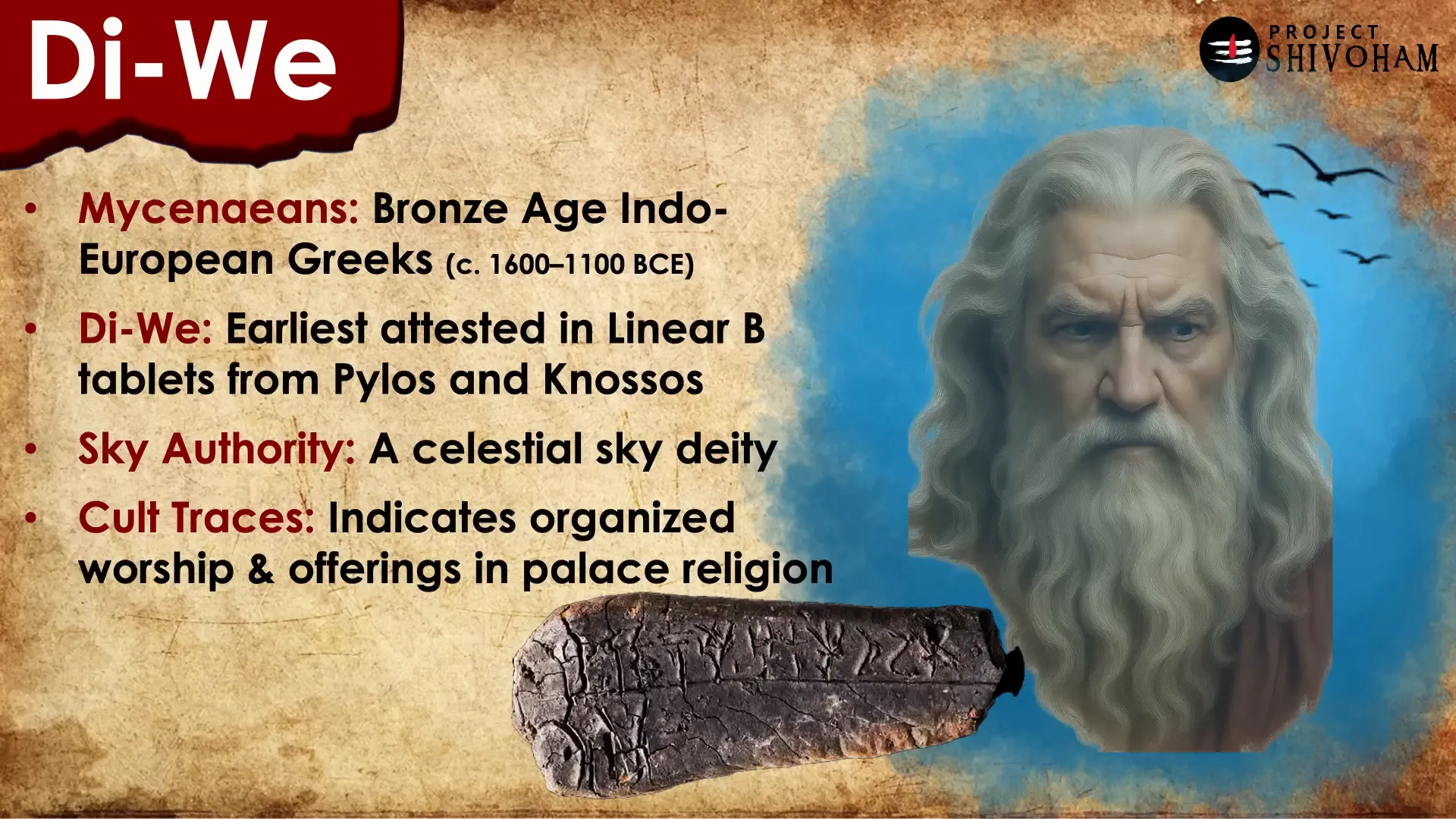

Our journey begins around 3,600 years ago, during the late Bronze Age, in the region now known as Greece. The Mycenaeans, early Indo-European people who preceded the classical Greeks, left behind enigmatic clay tablets inscribed in a script called Linear B. Among the inscriptions, a name stands out: Dhiwei, a sky deity revered as a divine authority from the heavens.

Dhiwei appears in the context of formal rituals, offerings, and cult activities, underscoring his importance as one of the oldest and most significant gods worshipped in the Mycenaean Greek region of Europe. This early recognition of a supreme sky god sets the stage for the evolution of this divine figure in later cultures.

Zeus: The Supreme Sky God of Early Greece

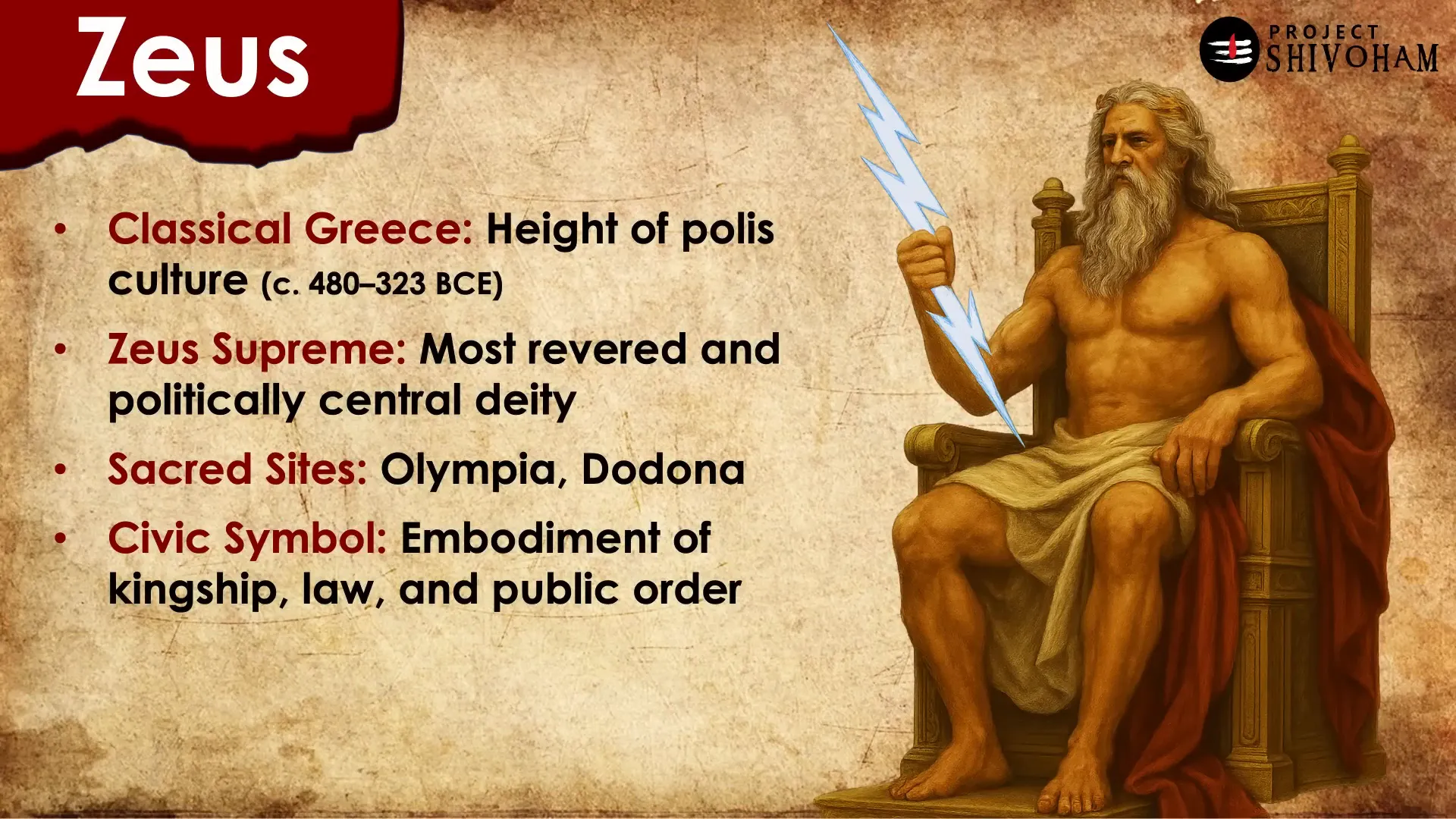

Fast forward to around 800 BCE, a period marked by the emergence of city-states and the gradual formation of the classical Greek identity. It is during this time that Zeus rose to prominence as the supreme sky god, depicted as the king of gods wielding thunder and dispensing justice. His portrayal in Homer’s epics reflects these attributes, drawing parallels to the Indian deity Indra, who is also associated with thunder and rulership.

However, it is important to clarify a common misconception: Zeus is not a form of Indra, despite the similarities. While both are thunder-wielding sky gods, their roles, worship practices, and mythologies differ significantly, a distinction that becomes clearer as we explore further.

Zeus was not worshipped in grand temples like later gods but was invoked in legal oaths, guest rituals, and public ceremonies. He bore many epithets — Olympios, Xenios, Horchios — reflecting his multifaceted roles, much like Indian deities who have multiple forms and titles depending on context.

Jupiter: The Roman Transformation of Zeus

By 500 BCE, the Romans adopted Zeus’s characteristics into their chief deity, Jupiter. Jupiter inherited Zeus’s divine authority over the sky, thunder, and law but came to symbolize Roman power, war, and governance. He was worshipped alongside other major Roman deities like Juno and Minerva, especially on the Capitoline Hill in Rome.

Jupiter’s influence extended beyond religion into astronomy, with the largest and brightest planet visible from Earth named after him, symbolizing his status as king of the gods.

Deipateros and Dheavas: Sky Gods of the Balkans and Baltic Regions

The worship of the sky deity was not confined to Greece and Rome. Around 3,200 years ago, in the western Balkans, the ancient Illyrians revered Deipateros, a sky god embodying cosmic order, thunder, storms, justice, and divine sovereignty. This deity shared many traits with Zeus and Jupiter, underscoring the widespread veneration of a paternal sky god among Indo-European peoples.

Similarly, in the Baltic tradition, particularly in Latvia and Lithuania, the sky god Dheavas was worshipped from around 1,000 BCE until the Christianization of the region in the 1200s. Unlike the more interventionist Zeus or Jupiter, Dheavas was a distant and passive ruler associated with light, order, and cosmic balance. Linguistically, Dheavas is a direct descendant of the proto-Indo-European sky god, preserving ancient traits of this divine figure.

These examples highlight the long-standing and widespread reverence for a sky father deity across various European cultures, each adapting the archetype to their unique cultural and environmental contexts.

The Common Thread: Dyauspater Across India and Europe

What unites these diverse deities is their shared origin in the ancient Indo-European sky god known as Dyauspater. This name appears in the Rig Veda, one of the oldest sacred texts of India, and is linguistically and conceptually linked to Zeus, Jupiter, Deopatros, and other names across Europe.

A compiled list of these deities reveals a remarkable continuity:

- Dyauspater — Rig Veda

- Zeus — Ancient Greek civilization

- Jupiter — Roman civilization

- Deopatathos — Balkans and Baltics

While this information is widely accessible, the deeper philosophical and cultural significance of this deity is often overlooked or misunderstood. To truly appreciate Dyauspater’s role, one must delve into ancient Hindu scriptures and Vedic traditions.

Understanding Pitru Devata: Ancestor Veneration and Vedic Deities

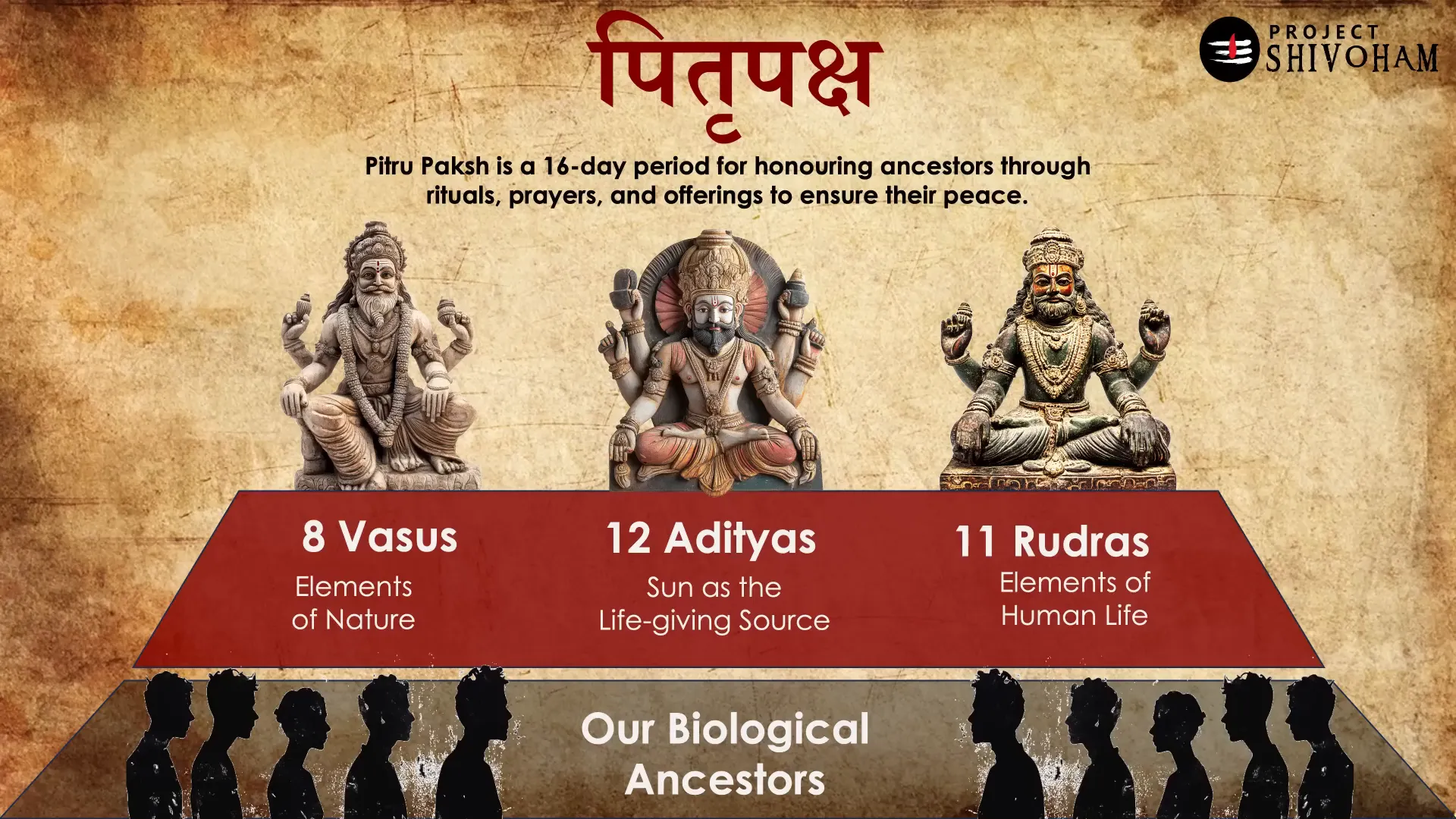

In Sanatana Dharma, the concept of Pitru Devata is central to ancestor veneration. While the term naturally evokes the image of departed ancestors, it is more complex and profound than mere remembrance of forebears.

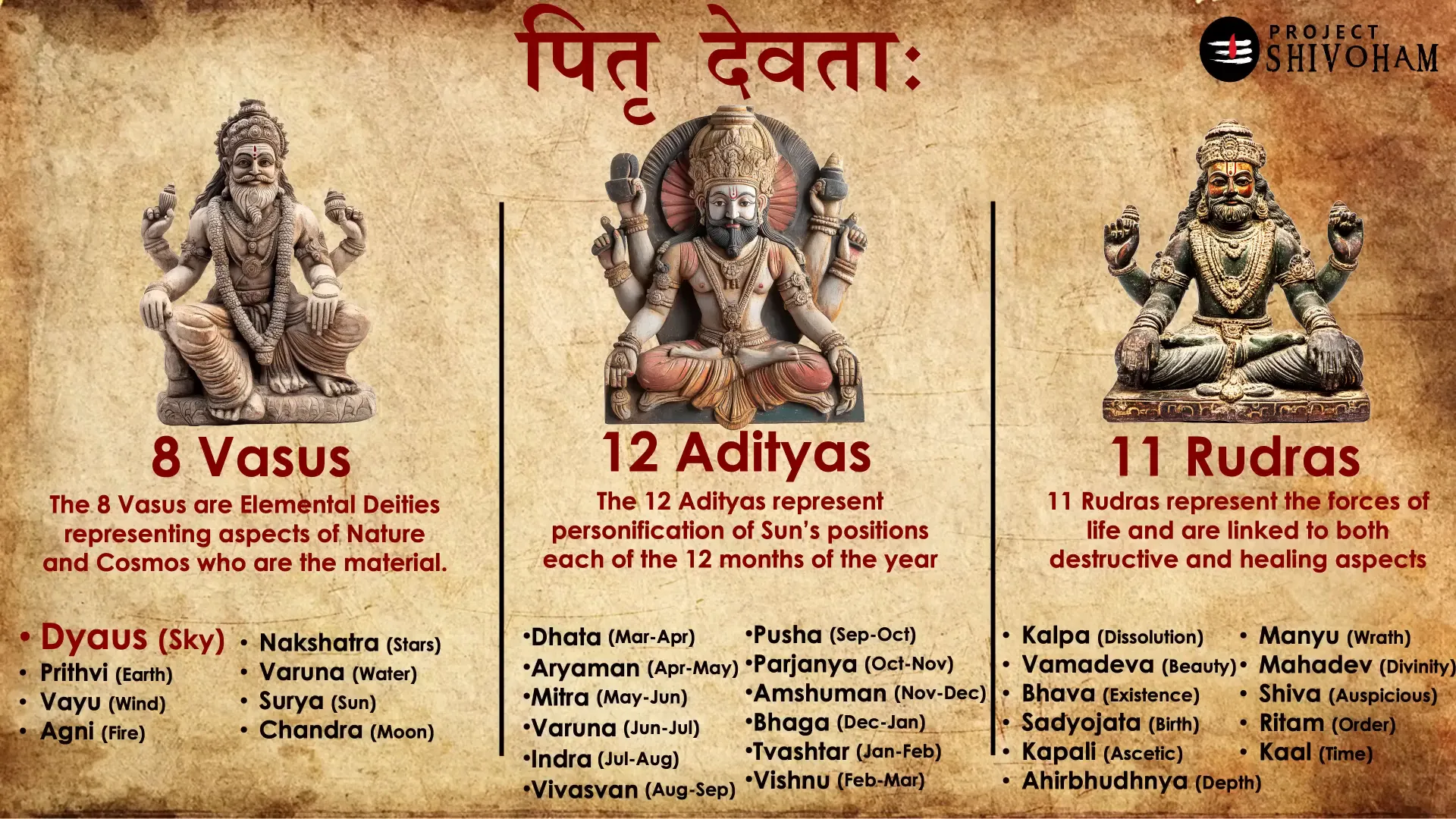

Pitru Devatas are actually a pantheon of Vedic deities divided into three groups:

- Vasus (8 elemental deities)

- Adityas (12 solar deities)

- Rudras (11 deities associated with life forces)

These groups collectively form the thirty-one Pitru Devatas, revered during the sixteen-day period of Pitru Paksha, a time dedicated to honoring ancestors through rituals and offerings before the festival of Diwali.

The eight Vasus represent elemental aspects of nature and cosmos, including sky, earth, wind, fire, stars, water, sun, and moon. Among them is Dyaus, the sky deity and one of the Pitru Devatas. This is the root of the name Dyauspater (sky father), which connects directly to Zeus and Jupiter.

The Twelve Adityas and Eleven Rudras

The twelve Adityas personify the sun’s position across the twelve months of the year, with names such as Dhaata, Aryaman, Mitra, Varuna, Indra, Vivasvan, and Vishnu. The eleven Rudras represent dynamic life forces, encompassing destructive and healing energies, with names like Kalpa, Vama Deva, Bhava, and Kapali.

Together, these groups symbolize the natural and cosmic order as well as the human life cycle, forming the foundation for the practice of ancestor veneration in Vedic culture. Our biological ancestors are believed to be absorbed into these elemental and cosmic forces after death, explaining why we honor both the natural elements and our forebears during Pitru Paksha.

Dyauspater and Bhishma Acharya: The Mahabharata Connection

A fascinating revelation emerges when we explore the Mahabharata, one of India’s greatest epics. The sky deity Dyauspater is none other than Bhishma Acharya, a central figure in the epic known for his wisdom and dharmic teachings.

In the Adiparvam section of the Mahabharata, specifically the Sambhava Parvam, the birth of Bhishma is described. Before his mortal incarnation, Bhishma was one of the eight Vasus — the elemental deities — specifically Dyaus Pitra. According to the narrative, Vasistha Maharshi cursed all eight Vasus to be born as mortal humans. Seven of these Vasus were born to King Shantanu and Ma Ganga, who killed them to redeem them from the curse, while the eighth, Dyaus Pitra, incarnated as Bhishma, who lived a long and influential life.

The curse and incarnation were ultimately a blessing, as Bhishma became the guiding force of the Mahabharata, imparting profound lessons on dharma (righteousness) and governance in the Shanti Parvam and Anushasanika Parvam.

The exact reference for this can be found in Mahabharata, Adiparvam, Chapter 99, verses 38 to 42, where the transformation of Dyauspater into Bhishma is detailed.

Dispelling Myths: Aryan-Dravidian Theory and Cultural Continuity

It is crucial to address some misconceptions surrounding the connections between ancient Indo-European and Indian traditions. The similarities between these cultures do not imply that ancient Europeans were following Hindu culture, nor do they suggest that the Vedas were brought to India from Europe or Central Asia.

Many indigenous cultures independently worshipped elements of nature such as rain, trees, mountains, the sun, and the moon, which does not necessarily indicate a shared origin. However, the Vedic tradition in Bharat (India) preserves not only the names but also the philosophies, rituals, and cultural contexts behind these deities, something largely lost in ancient European cultures.

This understanding challenges the baseless Aryan-Dravidian theory that some continue to believe without critical examination. The living and thriving worship of Dyauspiter in India during Pitru Paksha and the recitation of Vishnu Sahasranamam, attributed to Bhishma Acharya, are testaments to this enduring cultural memory.

The Enduring Legacy of the Sky Father Across Continents

To conclude, the ancient Indo-European sky father — whether called Dyauspater, Zeus, Jupiter, Deopatros, or Dheavas — represents a shared divine archetype that transcends geography and time. This radiant sky god, the bringer of daylight and wielder of thunder, was revered by many cultures across Europe and Asia over the last 3,500 years.

While myths and cultures evolved, the core essence of this deity endured as a living tradition in India and a historical artifact in Europe, where many temples and shrines bearing his legacy have been lost or destroyed.

Today, the worship of Dyauspiter continues in India during Pitru Paksha, and his memory lives on in the epic tales and rituals of Sanatana Dharma. In Europe, remnants of this once-unified divine idea linger in the stones of ancient temples, silently whispering the story of a shared human heritage.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Who was Dyauspater?

Dyauspater is the proto-Indo-European sky father deity whose name means “sky father.” He appears in various ancient cultures under different names such as Zeus in Greece, Jupiter in Rome, Deipateros in the Balkans, and Dheavas in the Baltic regions. In the Rig Veda, Dyauspater is a significant Vedic deity representing the sky and divine authority.

How is Bhishma Acharya connected to the sky deity?

According to the Mahabharata, Bhishma Acharya is the earthly incarnation of Dyauspater, one of the eight Vasus. Cursed by Vasistha Maharshi, the Vasus were born as mortals, and Bhishma’s birth as the eighth Vasu carries the legacy of the sky father, making him a living embodiment of this divine archetype.

Is Zeus the same as Indra from Indian mythology?

While Zeus and Indra share similarities as thunder-wielding sky gods, they are distinct deities with different mythologies, cultural roles, and worship practices. It is a misconception to equate Zeus as a form of Indra.

What is Pitru Paksha, and how does it relate to Dyauspater?

Pitru Paksha is a sixteen-day period in the Hindu calendar dedicated to honoring ancestors through rituals and offerings. During this time, the Pitru Devatas — comprising the eight Vasus, twelve Adityas, and eleven Rudras — are worshipped. Dyauspater, as one of the Vasus, is venerated as part of this tradition, connecting ancestor worship with cosmic elements.

Does the worship of Dyauspater in India mean ancient Europeans followed Hinduism?

No. While there are striking linguistic, cultural, and philosophical similarities between ancient Indo-European and Vedic traditions, this does not mean ancient Europeans practiced Hinduism. The shared worship of a sky deity reflects common Indo-European roots rather than direct cultural transmission.

What happened to the worship of the sky deity in Europe?

Many ancient European traditions that worshipped this sky deity have been lost or transformed over time, especially with the rise of Christianity. Temples and shrines dedicated to these gods often fell into ruin, and much of the original philosophy and practices behind the deity were forgotten.

Final Thoughts

The story of why Bhishma was worshipped in Europe is not just about a deity’s name or myth but about understanding a shared cultural memory that spans thousands of years and continents. It’s a reminder of how ancient civilizations, though separated by geography, were connected through common spiritual archetypes and cosmic understandings.

By examining the ancient texts, rituals, and historical evidence, we gain insight into the profound unity underlying diverse cultures and how the legacy of the sky father continues to inspire and inform spiritual traditions today.

This article was created from the video Why Bhishma was worshipped in Europe? with the help of AI. Thanks to Aravind Markandeya, Project Shivoham.