Table of Contents

- Overview: a strange, quiet avatar

- The big picture: avatars, function, and evolution

- Matsya as a lens for understanding Hayagriva

- First appearances of a horse-headed figure: Rigveda and Madhuvidya

- The Hayagriva Upanishad and Adharvana tradition

- Hayagriva in the Mahabharata: Madhu and Kaitabha

- Interpreting the Madhu-Kaitabha theme

- How Hayagriva is depicted: iconography and regional spread

- Buddhist Hayagriva: transformation into a wrathful protector

- Symbolic reading: what does the horse mean?

- Hayagriva and the three gunas: a concise map

- Why different texts tell different stories

- Iconographic details to notice

- Where Hayagriva worship survives today

- Hayagriva’s contemporary relevance

- Scenes revisited: tying each scriptural snapshot together

- Practical takeaways for seekers and students

- Selected quotations and condensed ideas

- Frequently asked questions

- Closing reflection

Overview: a strange, quiet avatar

Sri Mahavishnu’s avatars from Matsya to Rama and Krishna are familiar to most. Yet among those iterations there is one that remains enigmatic, little known and often misunderstood: Hayagriva, the horse-headed manifestation. The image of a deity with a horse head and human body raises questions. Why a horse? What is his role? How did different traditions — Hinduism and Buddhism — interpret the same figure so differently?

This article traces Hayagriva through the oldest sources, follows the evolution of the idea, explains the core symbolism, compares Hindu and Buddhist portrayals, and looks at the avatar’s iconography and modern relevance. Rather than getting lost in contradictory stories, the goal here is to read these narratives as symbolic expressions of a single truth: the protection and transmission of knowledge, and the victory of clarity over confusion.

The big picture: avatars, function, and evolution

The avatar concept did not spring up fully formed as a sequence of named incarnations. Early texts focused on acts and functions rather than on named deities. Over centuries, stories were retold, expanded and linked explicitly to Sri Mahavishnu. This process matters because it shapes how we read legends: are we looking at literal biography or layered allegory?

Take the Matsya episode. In the oldest source, the Shatapatha Brahmana, the entire Matsya story is compressed into six mantras: a little fish meets Manu, warns of a flood, grows rapidly under Manu’s care, leads Manu’s boat to safety, and life is re-established afterwards. There is no explicit naming of Vishnu in that primary account. Later Purana retellings explicitly identify the fish with Vishnu. The emphasis shifted from the salvific act to the divine identity behind it. That shift helps explain how the same protective force came to be seen across diverse texts as an avatar of Vishnu.

Matsya as a lens for understanding Hayagriva

Why begin with Matsya? Because it demonstrates an important method of Hindu mythmaking: a cosmic function (protection, preservation, transmission) becomes personified, and then that personification accumulates names, attributes and stories in later retellings. Hayagriva must be read in the same spirit. His earliest references are functional — a horse-headed manifestation associated with teaching and preserving sacred knowledge — and only later does a complex narrative matrix develop around him.

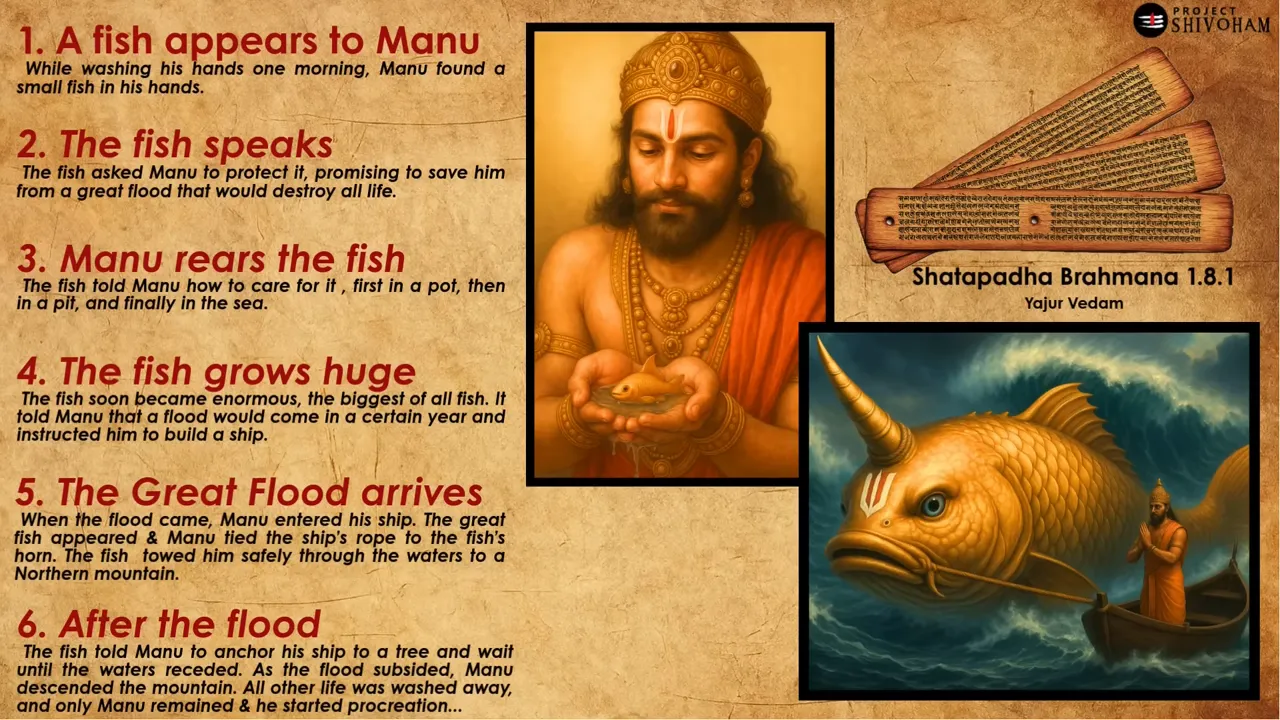

Six steps in the original Matsya account

- A small fish appears to Manu while he is washing his hands in the river.

- The fish speaks, asks for protection and promises to warn Manu of a coming deluge.

- Manu protects and nourishes the fish, which grows quickly.

- When the fish outgrows every vessel, Manu releases it into the ocean.

- At the appointed time the flood comes; Manu ties his boat to the fish and survives.

- After waters recede Manu re-establishes life on earth.

The Shatapatha Brahmana uses the episode to highlight the protective function that later traditions attribute to Vishnu. This pattern — act, then identity — prepares us for Hayagriva: a form that embodies the safeguarding and teaching of knowledge.

First appearances of a horse-headed figure: Rigveda and Madhuvidya

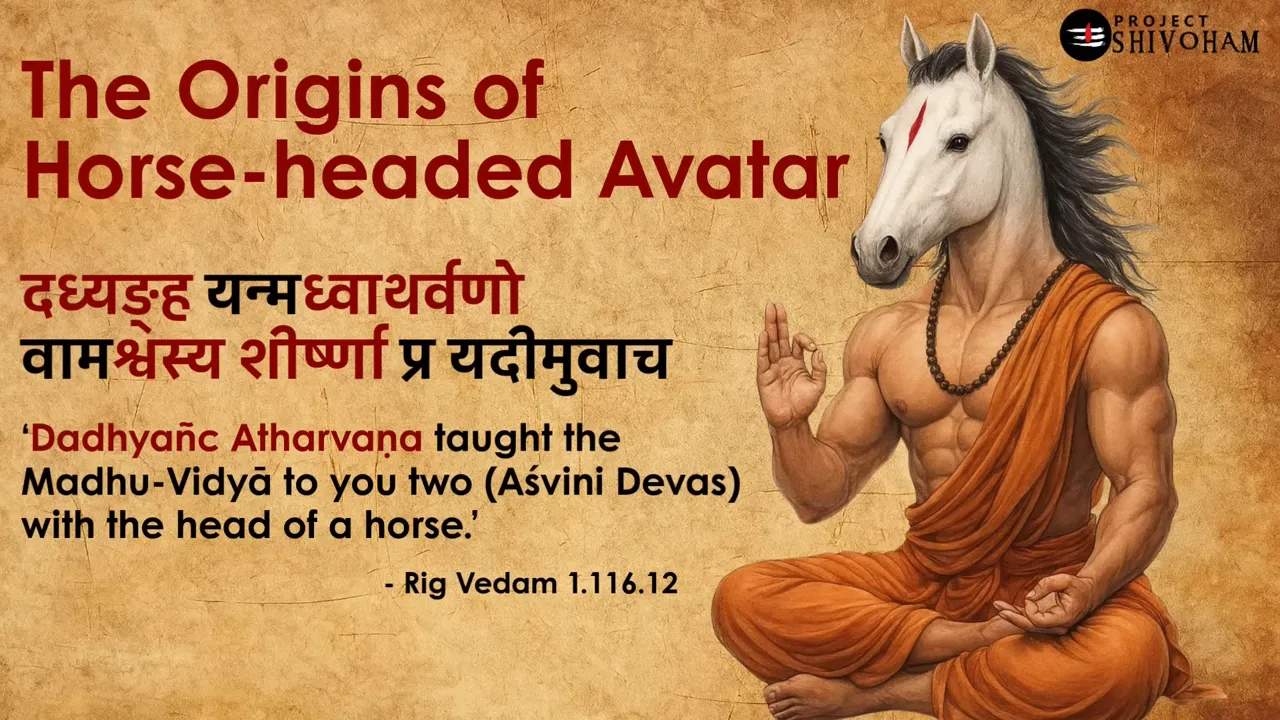

The earliest textual hint of a horse-headed divine figure appears in the Rigveda. A mantra records that Dadyankadarvana taught the Madhu Vidya to the Ashwini Devas “with the head of a horse.” This is not a dramatic avatar story in the later Purana sense; instead it is a cryptic, primordial image: a horse-headed teacher transmitting a special teaching. That teaching is Madhu Vidya.

Who is Dadyankadarvana?

Dadyankadarvana is a rishi identified with a sage whose memory survived in ritual and story. The name crops up as the transmitter of Madhu Vidya. The phrase “with the head of a horse” signals a focus: a horse-headed teacher, not merely a metaphor, is the earliest appearance of the horse-headed motif.

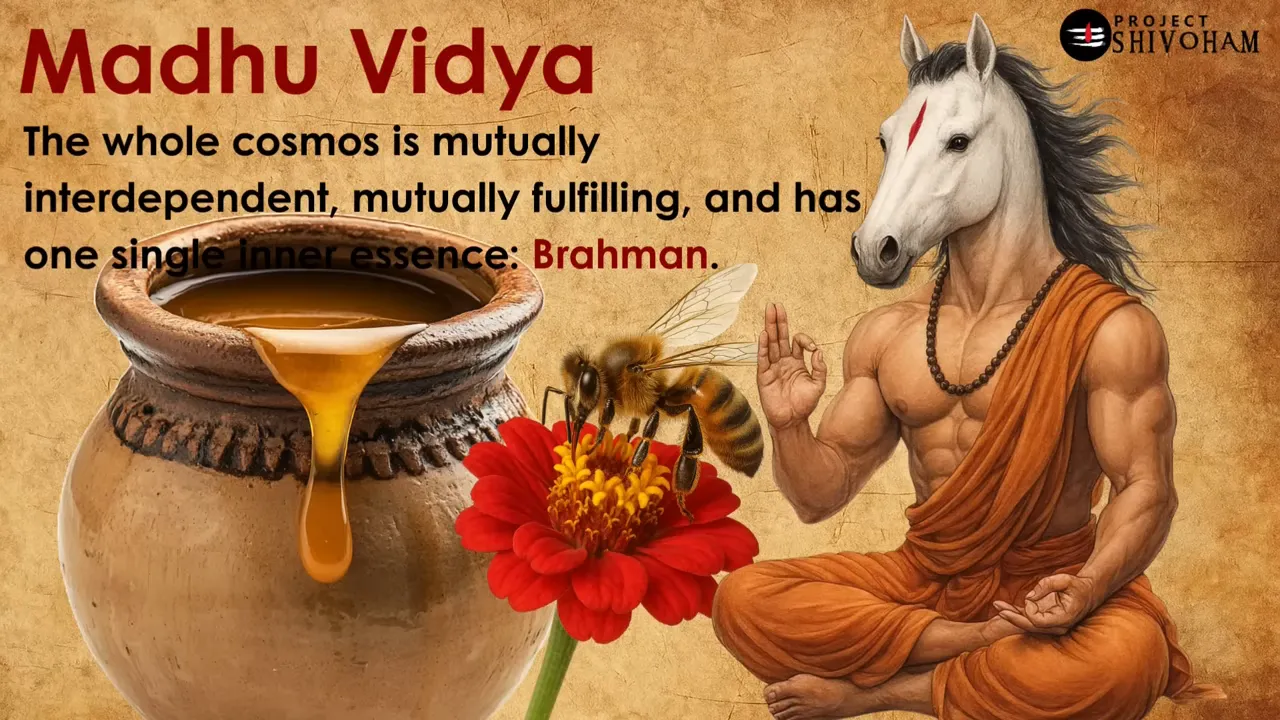

What is Madhu Vidya?

Madhu Vidya is an esoteric teaching about the unity and interdependence of the cosmos. The Rigvedic metaphor is simple and elegant: different flowers yield honey, but the honey is essentially the same. So too, the inner essence of all beings and natural elements can be understood as one single reality — Brahman. The teaching enumerates fourteen mutual relationships that show how the cosmic whole is self-reflective and interdependent.

Put plainly, Madhu Vidya asks us to see the world as a network of care and mutuality. It exhorts harmony with nature, compassion towards life, and an awareness of the single underlying reality that animates many forms. It is not merely intellectual doctrine. It is an attitude: respectful, integrative and wise.

The Hayagriva Upanishad and Adharvana tradition

The Adharvana, sometimes described as the youngest Vedic strand, preserves a fuller exposition of the horse-headed idea. In the Hayagriva Upanishad — found in that tradition — the form is explicitly named Hayagriva, Hayasiras or Mahashvassiris: the one with a horse head. The Upanishad treats the horse-headed form as a gnosis-bearing presence, explaining its purpose and the nature of the knowledge it represents.

Where the Rigveda gives us an early, allusive image of a horse-headed teacher, the Hayagriva Upanishad makes the figure a full-fledged subject of metaphysical instruction: an embodiment of that protecting, clarifying intelligence that safeguards the transmission of sacred knowledge.

Hayagriva in the Mahabharata: Madhu and Kaitabha

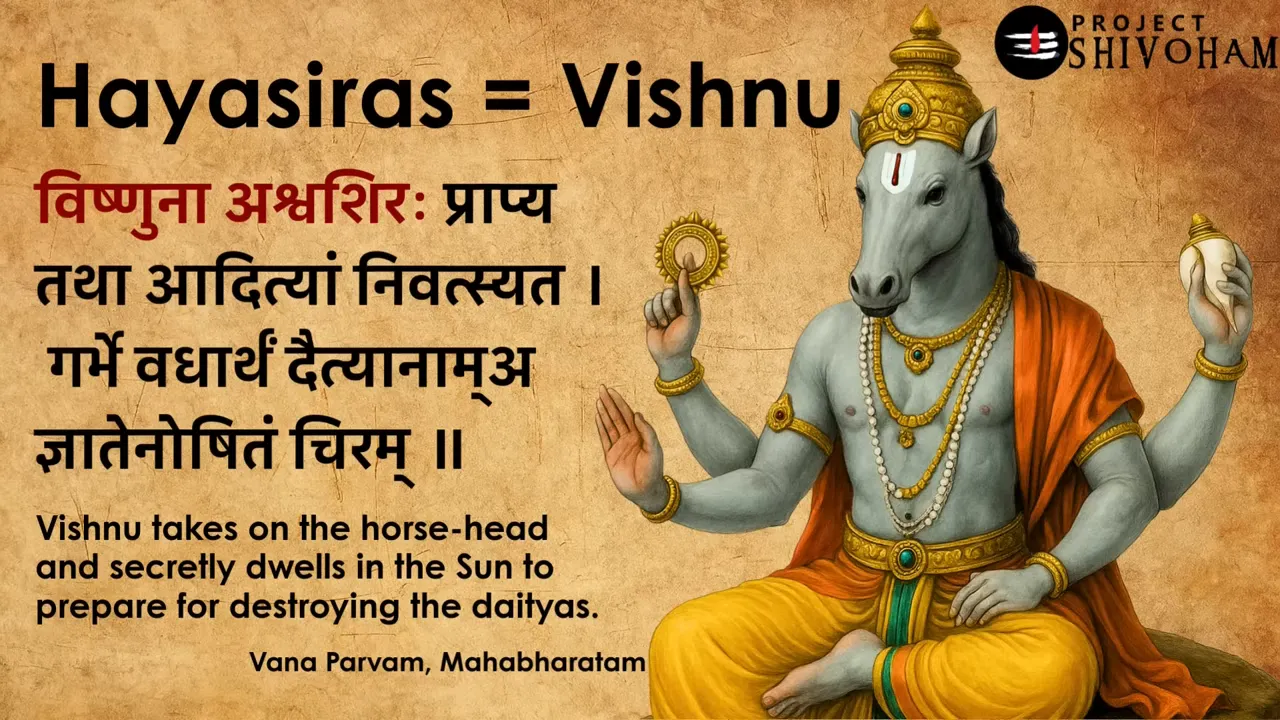

The Mahabharata expands the narrative further. Multiple sections, notably the Vanaparva and Shanti Parva, present a story in which Narayana creates two beings out of two drops of water: Madhu and Kaitabha. Each drop symbolizes one of the lower gunas. Madhu springs from tamas, the quality of inertia, ignorance and darkness. Kaitabha springs from rajas, the quality of activity, desire and restlessness.

These two demons come to represent psychological and spiritual obstacles. In several Puranic accounts they steal the Vedas — a potent mythic way of saying that when a person is governed by tamas and rajas, the capacity to perceive and preserve sacred knowledge is lost. Hayagriva’s role in these stories is to defeat Madhu and Kaitabha and restore the Vedas, meaning to restore the conditions under which true knowledge can be known and taught.

Why is this story striking?

Because in this avatar narrative Vishnu both originates and dispels the antagonists. That makes it one of the few stories in which the divine creates impediments and then removes them. Read symbolically, the lesson is intimate: the divine allows the potential for ignorance and restlessness to arise, and then intervenes in the form of wisdom to transform those tendencies. That is why one of Vishnu’s common epithets, Madhusudana — destroyer of Madhu — finds its context here.

Interpreting the Madhu-Kaitabha theme

The story is not about historical battles. It teaches about inner states. When tamasic and rajasic dispositions dominate, the life of the intellect and the heart becomes clouded. The “stealing of the Vedas” is an image: knowledge becomes inaccessible. Hayagriva restores the Vedas — knowledge is recovered — so people can live with clarity, compassion and harmony.

Different texts emphasize different things. The Rigveda and Hayagriva Upanishad present the horse-headed figure as a teacher of Madhu Vidya. The Mahabharata and later Puranas dramatize the dialectic, casting Hayagriva as the vanquisher of two internal foes. Both strands agree on the core truth: Hayagriva is about the protection and transmission of knowledge.

How Hayagriva is depicted: iconography and regional spread

Hayagriva’s iconography varies but a broadly accepted depiction emerges across time and space. The classical Hindu icon shows a horse head with a human torso, seated in padmasana or sometimes standing, often with four arms. Typical objects include a shankha (conch), chakra (discus), the Vedas and a hand in chin mudra or a blessing gesture. This arrangement highlights his dual role as both warrior of knowledge and meditative teacher.

Historically, Hayagriva worship was not limited to the subcontinent. Statues and reliefs from Cambodia and Indonesia indicate that the motif spread into Southeast Asia. Some Cambodian sculptures show a simpler, austere Hayagriva; Indian sculptures tend to be more ornate and carry additional attributes. Several surviving murtis are between five and eight hundred years old.

Over time iconography shifted in subtle ways. One pattern is the growing association of Hayagriva with Lakshmi, the goddess of prosperity and also the personification of knowledge’s sustaining power. In more recent depictions, Lakshmi may appear beside Hayagriva, reinforcing the idea that knowledge must be preserved in a field of abundance and care.

Buddhist Hayagriva: transformation into a wrathful protector

In Vajrayana Buddhism Hayagriva takes on a radically different guise. Here he is a wrathful dharma protector. The images are fierce, multi-armed and intimidating, with flaming hair, weapons and a horse element often depicted on the crown rather than as a literal horse head. He is not a serene teacher but a ferocious remover of obstacles — a deity invoked to cut through ignorance, fear and hostile forces obstructing spiritual practice.

Why the change in temperament? Symbolic clarity: Buddhism often uses wrathful forms to represent compassionate force. Where a gentle figure might fail to rouse a mind entangled in delusion, a terrifying form symbolizes the uncompromising energy required to break attachments. In that sense Hayagriva in Buddhism echoes the same core: elimination of hindrances and protection of the sacred. The expression is different, but the function is recognizable.

Shared symbolism across traditions

- The horse element marks speed, mobility and the thrust of knowledge into ignorance.

- Two subdued figures beneath the feet appear in both Hindu and Buddhist representations, indicating the crushing of negative powers.

- Objects associated with learning — Vedas in Hindu iconography, scriptures or ritual implements in Buddhist images — emphasize the preservation of doctrine.

These commonalities show how symbols migrate and adapt. A motif of a horse-headed teacher travels across religious landscapes and assumes forms that serve each tradition’s soteriological aims.

Symbolic reading: what does the horse mean?

The horse is rich in symbolic associations. As an animal it connotes vigor, speed, service and the capacity to carry. In Hayagriva the horse head can be read on several levels:

- Transmission and swiftness: the horse carries knowledge swiftly across obstacles.

- Discipline and harnessing: horses are trained creatures; the horse head indicates an ordered mind that can carry higher truth.

- Otherworldly witness: anthropomorphic-hybrid forms commonly mark threshold figures, mediators between mundane experience and transcendent truth.

When those symbolisms are combined with the theme of Madhu Vidya and the Madhu-Kaitabha narrative, Hayagriva becomes the emblem of an ordered, disciplined intelligence that rescues and transmits truth.

Hayagriva and the three gunas: a concise map

Gunas are the fundamental qualities that govern mental and moral states in classical Indian thought. They are:

- Tamas — inertia, confusion, dullness.

- Rajas — agitation, desire, unrest.

- Sattva — clarity, harmony, wisdom.

Madhu represents tamas; Kaitabha represents rajas. Hayagriva’s work is to quell both so that sattva can flourish. That is why the stories of slaying the demons and of teaching Madhu Vidya are two aspects of the same spiritual mission: restoration of a mind capable of insight.

Why different texts tell different stories

Across the Vedas, Upanishads, Mahabharata and later Puranas the stories shift because the aims of each text are different. The Rigveda murmurs allusive metaphors and focuses on teaching. The Upanishads systematize metaphysical meaning. The Mahabharata and Puranas dramatize moral and psychological struggles through epic narratives. Together they create a multilevel portrait of the same principle. Rather than seeing contradiction, we can read the variations as complementary: different genres, different emphases, same essential message.

Iconographic details to notice

- Hayagriva is frequently shown with four arms. Objects include conch, discus, Vedas and a hand in mudra.

- Seated in padmasana, the posture stresses Hayagriva’s role as a contemplative teacher as well as a preserver of knowledge.

- In some murtis an aksha mala appears, linking Hayagriva to ritual recitation and memory.

- In Buddhist images the horse element may appear as a mini-horse atop the crown and ferocious faces and weapons multiply to emphasize protective power.

Where Hayagriva worship survives today

While the worship of Hayagriva is not as widespread as that of many other avatars, pockets of devotion and iconographic legacies remain in India and Southeast Asia. In a few temples Hayagriva is still honored as a bestower of learning and a remover of obstacles. In Buddhist contexts practitioners call upon Hayagriva as a protector during advanced ritual practices meant to cut through obscurations.

The modern reverence for Hayagriva seems best suited to students, teachers and practitioners who wish to emphasize the safeguarding of learning and the forceful elimination of ignorance. Where rituals survive, mantras or recitations often accompany offerings and meditative practice.

Hayagriva’s contemporary relevance

We live in an information age yet struggle with misinformation, distraction and impulsive behavior. The Hayagriva motif — intelligence that protects, clarifies and reclaims truth from forces that obscure it — remains surprisingly timely. Whether we read it as a metaphor for disciplined education, a reminder to cultivate inner clarity, or a ritual figure invoked for protection, Hayagriva asks us to value knowledge not merely as data but as wisdom that sustains life in a balanced way.

That is why the horse-headed figure matters beyond antiquarian interest. It embodies an ethic: knowledge should be preserved, taught with care, and defended against internal and external forces that would corrupt or obscure it.

Scenes revisited: tying each scriptural snapshot together

The textual scenes are distinct but interlinked:

- Rigvedic image: a horse-headed teacher transmits Madhu Vidya, revealing the unity of things.

- Hayagriva Upanishad: an Upanishadic exposition makes the horse-headed form a living school of metaphysical instruction.

- Matsya precedent: the protective, salvific action that later becomes an avatar motif.

- Mahabharata dramatization: Madhu and Kaitabha embody tamasic and rajasic obstacles which the horse-headed form vanquishes to reclaim the Vedas.

- Buddhist transformation: the same protective impulse appears as a wrathful guardian who forcefully removes obstructions on the path.

- Iconographic evolution: sculptures in India and Southeast Asia show regional interpretations and emphasize either contemplative teaching or fierce protection.

Reading the scenes together makes clear that Hayagriva is less an oddity than a coherent symbol: the defender and teacher of true knowledge, adaptable across times and traditions.

Practical takeaways for seekers and students

- Value knowledge as a living practice, not mere accumulation.

- Recognize inner obstacles: dullness and agitation will hide insight unless disciplined attention is cultivated.

- Use symbols like Hayagriva not as literal talismans but as reminders of what must be preserved and defended: clarity, compassion and harmony.

- Appreciate cross-cultural forms: the same archetype can serve as serene teacher or fierce protector depending on the needs of practice.

Selected quotations and condensed ideas

“The essence is the same: when tamasic and rajasic qualities are quelled, people gravitate towards rightful knowledge.”

“Hayagriva ultimately represents the victory of sattva over tamas and rajas, and the reminder that true strength lies in wisdom.”

Frequently asked questions

Who is Hayagriva and what does the name mean?

Hayagriva literally means ‘horse-neck’ or ‘horse-headed’. He is an avatar or manifestation associated with Vishnu who appears with a horse head and human body. Across texts he embodies the protection, preservation and teaching of sacred knowledge.

Is Hayagriva mentioned in the Vedas?

Yes. The earliest hint appears in the Rigveda where a horse-headed figure named Dadyankadarvana teaches Madhu Vidya to the Ashwini Devas. The Adharvana/Hayagriva Upanishad later gives a fuller Vedic-period treatment of the figure.

What is Madhu Vidya?

Madhu Vidya is an esoteric teaching about the essential unity and interdependence of the cosmos. Using the honey-and-flowers metaphor the teaching explains how diverse forms share a single inner essence, and it spells out mutual relationships demonstrating interdependence.

How does the Matsya story relate to Hayagriva?

Matsya illustrates a pattern: a protective act later identified as Vishnu. Matsya’s original telling focuses on the salvific action and not on a deity’s name. The same pattern applies to Hayagriva: an early image of a horse-headed protector and teacher later becomes woven into the avatar framework connected to Vishnu.

Who are Madhu and Kaitabha?

In Mahabharata and later Puranic accounts Madhu and Kaitabha are two demons created from drops of water by Narayana. They represent tamas (inertia and ignorance) and rajas (agitation and desire) respectively, and Hayagriva vanquishes them to restore the Vedas — symbolically recovering knowledge obscured by these forces.

Why is Hayagriva portrayed as calm in Hinduism but wrathful in Buddhism?

Different traditions adapt shared symbols to their needs. Hindu portrayals emphasize Hayagriva as a calm teacher and preserver of knowledge. Vajrayana Buddhism transforms the motif into a wrathful protector, symbolizing fierce compassionate force that breaks attachments and clears the path for realization. The underlying function — removal of obstacles and protection of doctrine — remains consistent.

What are the common iconographic features of Hayagriva?

Common features include a horse head with a human body, four arms often holding conch and discus, one hand in chin mudra, and one holding the Vedas. He may be seated in padmasana or standing. In Buddhist images the horse may appear atop the head and the figure may be multi-faced and multi-armed, standing on subdued enemies.

Is Hayagriva worshipped anywhere today?

Yes, though not as widely as some other avatars. Devotional pockets exist in India and historical sites in Southeast Asia attest to earlier worship. In Buddhist regions Hayagriva survives as a protector deity invoked in specific ritual contexts.

What lessons does Hayagriva offer modern seekers?

Hayagriva encourages disciplined learning, protection of truth, and the cultivation of clarity. He warns that ignorance and agitation can hide wisdom and invites practices that cultivate sattva — calm, insight and moral harmony.

How should Hayagriva’s stories be read — literally or symbolically?

Both approaches are possible, but reading the stories symbolically often yields the most practical insight. The narratives function as mnemonic and moral devices that teach about inner states and the recovery of knowledge rather than as historical chronicles.

Closing reflection

Hayagriva is an example of how a powerful symbol can travel, change and yet remain faithful to a single mission. From a horse-headed teacher in the Rigveda to an Upanishadic guardian of Madhu Vidya, from an epic vanquisher of inner demons in the Mahabharata to a wrathful protector in Vajrayana Buddhism, Hayagriva across traditions calls us to protect and cultivate knowledge, to discipline the mind, and to transform lower tendencies into a stable, luminous intelligence.

Whether invoked as a serene guru or a ferocious guardian, Hayagriva reminds us that the highest strength is wisdom, and that wisdom must be both taught and defended.

This article was created from the video Why Vishnu took the Horse Avatar? with the help of AI. Thanks to Aravind Markandeya, Project Shivoham.